|

Garment Industry in Bangladesh: An

Era Of Globalization And Neo-Liberalization

Anam Ullah

Correspondence:

ASM Anam Ullah

BBA, MCOM (HRM&IR) University

of Western Sydney (UWS)

PhD Candidate- The University of Newcastle

(UoN) Australia

Email:

russell_adib@yahoo.com.au

Abstract

The forces of globalization and neo-liberalization

have sparked an ongoing debate between

developed and developing countries

regarding adherence to international

labour standards in international

trading agreements. Globalization

has been playing an important role

to many developing nations in changing

of its socio-economic structure. In

Bangladesh, economy moves from aid

to trade. Bangladesh became the 2nd

largest apparel exporting country

in the meantime. During the fiscal

year 2010-2011 garment exports totalled

US$ 20 billion, a 43% increase over

the previous year. In the global trade

system, a garment could be designed

in New York, made of fabric woven

in China, spread and cut, and sewn

in Bangladesh, and marketed in Australia.

This is the chain of global trade

and Bangladesh is enjoying its positive

outcomes at every stage of transactions

with the modern and developed countries.

However, here, the gruesome face of

neo-liberal free trade is all too

apparent as the corporate hunt for

ever cheaper labour drives low wages.

Therefore Bangladesh has received

its advantage in many ways. During

the 1980s and 1990s, economic globalization

enhanced by advancements in technology

led to the creation of multinational

companies. Besides, North American

Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and World

Trade Organization (WTO) agreements

contributed in an extensive form to

the creation of the garment industry

in Bangladesh through the proposed

elimination of trade quota by 2005,

which had a significant influence

on the Bangladeshi garment owners

to create more businesses in the country.

Being a provider of cheap labour,

Bangladesh has become an advantageous

destination of multinational companies,

especially in a labour intensive garment

industry. But this raises questions

of whether garment workers in Bangladesh

are adequately protected under globalization.

Design/ methodology/ approach:

The research technique has used

secondary data, collected through:

Literature review, Case studies in

various countries, Journals, Research

articles, Newspapers, Online news

and survey reports, BGMEA Yearly report

and other publications. The data was

collected through a number of different

methods.

Findings: Bangladesh (national)

GDP greatly relies on the apparel

industry at this moment. The increase

in garment trade within the NAFTA

could be shown a correlation between

the incensement of garment industries

and free access to the duty-free market.

Due to huge market access through

the Multi-Fibre Agreement (MFA) of

the General Agreement Tariff and Trade

(GATT) after the quota restriction

was abolished in 2005 - globalized

and liberalized trade policy strenuously

helped in growing garment industries

in Bangladesh. However neo-liberalization

and globalization increased production

and employment through exploitation

and insulated an antagonistic milieu

within developing nations especially

in Bangladesh. Under the ILO conventions,

where Bangladesh is signatory it is

mandatory to follow international

labour standards, but in a mind of

losing market share, the state is

not implementing such law and ignominiously

not producing a dynamic labour law

and is continuously offering corporate

abundant cheap labour.

Originality/ value/ objective

of this study: The value and objective

of research paper is assessing the

correlation between NAFTA and MFA

on the development of the garment

industry in Bangladesh. This study

shows the specific impact of neo-liberalization

and globalization on the garment industry

in Bangladesh and its positive and

negative impact on national labour

law and its implementation.

Key words: Garment industry

in Bangladesh, NAFTA and MFA, globalization,

neo-liberalization, labour standard,

labour law in Bangladesh, social justice

and human rights, the WTO and the

ILO.

1. Introduction

What begun to occur in the last quarter

of the twentieth century was the breakup

of the dominant nation state-based

economic model as what we now call

globalization kicked into gear (Munck,

2010). Friedman (2007) assertively

pointed in his study that "globalization

is an important factor that influences

organizations that compete for customers

with high expectations for performance,

and low cost". Since globalized

trade era begun, the international

economy found its new dimension towards

capital transformation within states

and of course it took to the international

frontier with a mind of "super

exploitation". Unequivocally,

its glaring compartmentalization in

the free-trade agreement, provided

a complete emancipation towards hunting

corporate cheap labour in the South-Pool,

and the real nexus of this ambience,

Bangladesh as a country, and the garment

industry in Bangladesh, not exception

in this case (see Islam & McPhail,

2011; Majumder & Begum, 2000;

Friedman, 2007; Rock, 2010). With

a population of 160 million people,

a small GDP, but steadily increasing,

and fledgling export market, Bangladesh

is perhaps an unlikely candidate for

cutting-edge experiments in linking

trade with labour rights.

Nevertheless, from the mid-1970s

to the mid-2000s, the global trading

of textile and garment products was

conducted under the terms of the Multi

Fibre Agreement (MFA), which was eventually

replaced, in 1995, by the Agreement

on Textiles and Clothing (ATC), which

was set to terminate from the trade

agreement at the end of year 2004.

The North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA) between the USA, Canada and

Mexico was implemented in 1994, which

Tsang and Au (2008) found in their

study, and tariff was completely abolished

from 2005 (see Beresford, 2009; Chorev,

2005; Islam & McPhail, 2011; Majumder

& Begum, 2000; Asuyama, et al.

2013). On April 15, 1994, after eight

years of bitter and blatant negotiations

and constant crises, representative

of 108 countries met in Marrakesh,

Morocco, and signed the Uruguay Round

Agreements (Chorev, 2005).

However, though the international

garment industry has had its own long

history, eventually a new era began

after assuage of trade barriers, which

is also known as the free-trade liberalization

era. While the international garment

trade was liberalized after 2004,

a new dimension of international economy

emerged too. Corporate cheap labour

was hunted strenuously during this

period (see, Truscott, Brust &

Fesmire, 2007. In this process, most

advanced developing nations like China

and Vietnam benefited indeed. However,

due to some practical reasons, Bangladesh

started enjoying quota free access

to the US and EU market, which was

the golden period for Bangladeshi

garment producers. In other research

it was found that low exports benefited

from the quotas imposed on the large

exports. As a result of this, many

developing nations like: Bangladesh,

Cambodia, Pakistan, Sri-Lanka benefited

from such facilities (see Asuyama,

et al. 2013 & Beresford, 2009).

Research shows that China became

the world leader in the apparel industry

in the meantime, by 2009, when US

quantities restrictions on Chinese

imports were due to end, many researchers

in this filed grandiosely assumed

that, the least developed and small

nations would have been affected in

the world and regional competition.

But, however, in Bangladesh, the situation

was absolutely favorable and such

polemic assumption was completely

demystified after receiving huge orders

from the world's best retail groups

like: Wal-Mart, Nike, Gap, though

these organizations had to face tremendous

criticisms for workers' exploitation

in Bangladesh (Islam & McPhail,

2011). In the event, the establishment

of export-oriented garment manufacture

in Bangladesh led to the entry of

a whole generation of young, unmarried

females, mainly from rural areas,

into the industrial labour force (Rock,

2010). First World countries are attracted

to production sites through the WTO's

liberalized free-trade globalization

system in the Third World that offered

low cost and low trade union participation.

Third World proles are also perceived

as the victims of capitalist expansion

who have little power to respond to

exploitation, rather than treating

the working class as a social force

in history (Rock, 2010).

April 24, 2013, the building collapse

of Rana Plaza warned us again to be

aware of global economic agendas that

drastically subverted worker's human

rights and social harmony and unduly

led to increased social cacophony

in Bangladesh. Workers are howling

for working conditions and minimum

wages that have never been implemented-though

Bangladesh government enacted labour

law in 2006, and modified in 2010

and 2013 respectively under pressure,

both from the national and international

perspective. Bangladeshi garment industry,

a hundred percent export-oriented

sector, experienced phenomenal growth

during the last 20 years or so, accumulating

more than 80 percent of its total

merchandise export (Garwood, 2011,

p.18; Mahmud 2008, p.260; Ahmed, 2004;

Majumder & Begum, 2000; BGMEA,

2013).

Currently Bangladesh has become the

2nd largest apparel exporting country

in the world. During the fiscal year

2010-2011, Bangladesh exported RMG

totaling from US$ 6.8 billion to US$19.9

billion in 2012, a 43 or more percent

increase over the last couple of years

and recording a compound annual growth

of 16.6 percent. By the year 2012-2013,

the country exported RMG totaling

US$ 20 billion and was deemed to be

gained 45 to 50 billion by the year

2020 (BGMEA, 2013). If globalization

provides the backdrop for drama, the

achievements of the garment industry

in Bangladesh are indeed dramatic

(Ahmed, 2004). The country has more

than 6000 RMG factories with about

4 million workers (including 80 percent

women workers and almost another 20

million people directly or indirectly

engaged in this industry). This workforce

is primarily coming from rural communities

and extensively contributing to the

Bangladesh economy (BGMEA, 2013; Ahmed,

2004; Mahmud, 2008; Majumder &

Begum, 2000).

As I mentioned early that global

factors worked closely towards the

development of the Bangladeshi garment

industry, and one of the major factors

that took very significant place in

this regard as China shifted from

archetypal business to high-tech businesses

in the beginning of the current century,

worked as a key factor to success

of the Bangladeshi garment industries'

indeed (BGMEA, 2014). Thus, most retailers

shifted from China to the further

South, and Bangladeshi local, dynamic

and energetic new entrepreneurs started

developing relationships with international

buyers by offering high commitment

which is very important in trade relationships,

and also by offering cheap abundant

labourers-who had no social status

in the past in Bangladesh (see Majumder

& Begum, 2000; Rahman, 2004; Ullah,

2014). The key analysis of this study

would be conducted in two ways. First,

we will look at development in the

garment industry in Bangladesh; hence

we need to consider a few factors

in analysis, especially, key to analysis

how global capital made changes in

the garment industry and its socio-economic

development in Bangladesh. Second,

we will try to find how Bangladesh

got advantage in the era of globalization

and neo-liberalization, and how global

capital geo-politically obstructs

in the creation of potential labour

law in Bangladesh and its proper implementation,

and what is the role of the ILO since

1972, notwithstanding Bangladesh ratified

all fundamental conventions in the

meantime, but there is a huge gap

in implementation of such laws.

2 Literature

Review

2.1 Brief background of Bangladesh

Modern Bangladesh forms the Bengal

delta region in the Indian subcontinent,

where civilization dates back more

than 4,300 years. The early history

of the area featured a succession

of city states, Indian empires, internal

squabbling and a tussle between Hinduism

and Buddhism for dominance. Islam

arrived in late-classical antiquity

and dominated the society (Banglapedia,

2013). The borders of present-day

Bangladesh were established during

the British-partition of Bengal and

India in 1947, when the region became

East Pakistan, part of the newly formed

State of Pakistan. It was separated

from West Pakistan by 1,600 km of

Indian Territory. Due to political,

economic and linguistic discrimination,

popular agitation and disobedience

grew against the Pakistani State.

The Bengali people increasingly demanded

self-determination, culminating in

the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.

The new State, the People's Republic

of Bangladesh, was founded as a constitutional,

secular, democratic, multiparty, and

parliamentary state. After independence,

Bangladesh endured widespread poverty

and famine, as well as political turmoil

and military coups. The revitalization

of democracy in 1991 has been followed

by economic progress and relative

political calm, although the country's

two main political parties, the Awami

League and the BNP, remain highly

polarized and often at confrontational

loggerheads (Ullah, 2013; Rahman,

2011).

Many international scholars vividly

found in their research that, since

independence, the economy of Bangladesh

was fully dependent on traditional

agriculture as most of the people

lived in rural areas (Rahman, 2004).

The economy was mostly dependent on

foreign aid. But the government had

strong aspirations towards relegation

of poverty and boosting the economy.

By producing sufficient food it could

attain self-sufficiency, thus the

agriculture sector was preferred at

that time. But jute and tea industry

seemed as major exports from Bangladesh

at that time too. While the jute industry

has fully fallen into a moribund situation

and sharply declined its production

in early 1986, attention was given

to another forming sector, and the

garment industry was one of them in

which huge meditation provided for

its leverage (See Rahman, 2004).

2.2 Preceding history of textile

industry in Bangladesh 17th-18th century

At the very outset we need to consider

analyzing the roots of this industry

the way it was developed and its proper

delineation. Bengal cotton fabrics

were exported to the ancient Roman

and Chinese empires in the early centuries.

Dhaka Muslin became famous and attracted

foreign and transmarine buyers after

the establishment of the Mughal capital

at Dhaka [1556-1605]. A widely used

term for high-quality, pre-colonial

Bengal textiles, muslin was manufactured

in the city of Dhaka and in some surrounding

stations, by local skilled workers

with locally produced cotton, attaining

fame as Dhaka Muslin (Ross, 2003).

In the 17th century, the European

companies came and established their

settlements in Bengal, leading to

the demise of the Bengal Muslin Industry

(Ross, 2003). During the 18th century,

the British imposed high tariffs on

Bengali textiles (for centuries previously,

the leader in international trade)

in order to protect its own rising

industries in Lancashire and the West

of Scotland (Ross, 2011, p.230).

2.3 Modern history of garment

industry in Bangladesh 1970-2014

Bangladesh garment industry traversed

its long river from 1970-2014. Unequivocally

this prominent sector has gone-through

by facing many challenges nationally

and internationally. This prominent

and blatant industrial sector grappled

much polemic debate at the national

and international levels. But, however,

due to some facts, still this organization

is undergoing sardonic debates over

its working conditions and very low

wages, which is very inimical indeed

in regard to analysing such phenomenon

under the current circumstances. Many

from national and international advocacy

groups and the ILO are strenuously

concerned about its working conditions

and labour rights along with other

issues that we need to investigate

in our literature review next.

As we know exporting garments has

been a first step for industrialization

and economic growth for many low-income

countries with abundant and inexpensive

labour (see Asuyama, et al. 2013).

After the Second World War, East Asian

Countries such as Honk Kong, Taiwan,

South Korea and later, China and Vietnam,

and other developing nations simultaneously

developed the apparel sector by direct

assistance from different countries

like US and the European Union. In

the mid-1990s, even least developed

countries such as Bangladesh, Cambodia

and Madagascar have rapidly increased

their garment exports (Asuyama, et

al. 2013). But by the last two decades

or so, Bangladesh has changed its

economic condition by producing the

world's best garments which has more

than 10% economic contribution to

the national GDP along with changing

the nation's status quo from aid to

trade BGMEA (2014) and looking to

becoming a middle earner country by

the end of 2020.

It can be said that Bangladeshi garment

industries were fully underpinned

by foreign investment indeed. The

hundred percent export-oriented RMG

industry experienced phenomenal growth

during the last 20 or so years. In

1978, there were only 9 export-oriented

garment manufacturing units, which

generated export earnings of hardly

one million dollars (Mottaleb &

Sonobe, 2011). Some of these units

were very small and produced garments

for both domestic and export markets.

Four such small and old units were

Reaz Garments, Paris Garments, Jewel

Garments and Baishakhi Garments. Reaz

Garments, the pioneer, was established

in 1960 as a small tailoring outfit,

named Reaz Store in Dhaka. It served

only domestic markets for about 15

years. In 1973 it changed its name

to M/s Reaz Garments Ltd. and expanded

its operations into export market

by selling 10,000 pieces of men's

shirts worth French Franc 13 million

to a Paris-based firm in 1978. It

was the first direct exporter of garments

from Bangladesh. Desh Garments Ltd,

the first non-equity joint-venture

in the garment industry was established

in 1979 (Mottaleb & Sonobe, 2011).

Bangladesh was not subject to export

restrictions under the (MFA), which

was the main reason to invest capital

in Bangladesh in a joint collaboration

program with Desh Garment. It was

a significant moment for any local

company for jubilation after receiving

offers from one of the modern and

reputed trade organizations from South

Korea, and Bangladesh absolutely gyrated

in this matter (Mottaleb & Sonobe,

2011; Ahamed, 2013).

The Daewoo Corporation had restriction

in exports under the quota system;

hence technical and marketing collaboration

with Daewoo Corporation of South Korea

and Desh Garment in Bangladesh was

accorded in a common interest of trade

(Mottaleb & Sonobe, 2011). It

was also the first hundred percent

export-oriented company. It had about

120 operators including 3 women trained

in South Korea, and with these trained

workers it started its production

in early 1980. However, the emergence

in the 1970s and subsequent success

of the export-oriented garment industry

ushered in a new social reality for

Bangladesh (Rock, 2003). Not only

did it mark the entry of new young

Bangladeshi women into this formal

manufacturing employment for the first

time, it also incited determined attempts

by these workers to form unions, something

extensively unthinkable in the past

because of the presence of rigid forms

of control through the socially sanctioned

norms of purdah or female seclusion

( Rock, 2003).

When Desh Garment was established

in 1979, the government of Bangladesh

hardly recognized the potential of

the garment industry. In 1982, however,

the government had begun to offer

various incentives to the garment

industry such as: duty-free import

machinery and raw materials, bonded

warehouse facilities and cash incentives

(Mottaleb & Sonobe, 2011). Another

South Korean Firm, Youngones Corporation

formed the first equity joint-venture

garment factory with a Bangladeshi

firm, Trexim Ltd. in 1980. Bangladeshi

partners contributed 51% of the equity

of the new firm, named Youngones Bangladesh.

It exported its first consignment

of padded and non-padded jackets to

Sweden in December 1980 (Bangla-pedia,

2013)

2.4 Scenario of NAFTA - WTO -

MFA -ATC in Bangladeshi garments

An important policy which affected

considerably the global Textile and

Clothing (T&C) trade in the past

decade is the (ATC). Asuyama, et al.

2013 assertively found in their study

that by agreement it was decided to

abolish quota status gradually within

the next ten years from 1995 to 2005,

which agreement was accomplished with

a clear agenda - on April 15, 1994,

after eight years of bitter and blatant

negotiations and constant crises,

representatives of 108 countries met

in Marrakesh, Morocco, and signed

the Uruguay Round Agreements (Chorev,

2005).

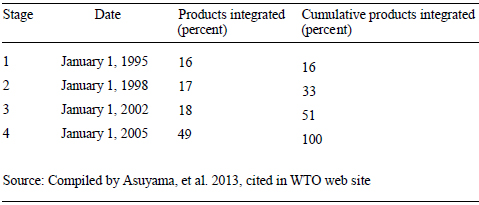

Table 1: shows integrations procedures

of textile and clothing under ATC

The above table shows how gradually

the quota system was weaned from 1995

to 2005. Nevertheless high tariff

was imposed on East Asian countries

in North American markets but relaxed

for NAFTA members within the Free

Trade Agreement (FTA) (Asuyama, et

al. 2013). This model was designed

to gear up the trade relationship

between NAFTA members and increase

economic power within the region.

However, in the meantime, China, Bangladesh,

Cambodia and some other nations became

competitive clothing exporters, enhanced

by offering their cheap and abundant

labour force. In this category, nowadays,

the majority of the large clothing

exporters are located in Asia, and

Bangladesh got the second position

in the world ranking in this category

(Mottaleb & Sonobe, 2011).

Based on World Trade Organization

(WTO) trade statistics, ten of the

South and South-east (S&SE) Asian

countries including: India, Indonesia,

Thailand, Philippines, Sri Lanka,

Pakistan, Malaysia, Singapore, Bangladesh

and Vietnam have been the biggest

US suppliers during the last decade

or so, but China was not included

in the list though China is the largest

single US T&C importers (Asuyama,

et al. 2013). But by year of 2009,

China's quota restriction was removed

once again and continued to supply

T&C to the US market full of strength.

Moreover, another interesting research

finding on this issue has been revealed

in the meantime which is: by the third

stage of quota integration for quota

liberalization from 2002 to 2004,

a total of 51 percent of developed

countries' imports were freed from

quota restrictions. Soon fully quota

restrictions were abolished and most

developed countries' investors moved

to the South. Global capital started

moving with its blatant agenda to

maximize profit by exploitation of

cheap abundant labour, which is seemed

as more shoddy, impersonal and inhuman

business than a compliant business

in the 21st century. Due to word limitations

we cannot elaborately discuss global

capitalism and its despicable agenda

more precisely but, notwithstanding

we would try to reveal a current example

of forced labour tragedy being held

on April 24, 2013 at Shaver near the

capital city of Bangladesh where almost

1,135 poor workers were killed and

other more than 3000 workers were

permanently disabled, a clear sign

of dehumanization indeed.

(NAFTA) and World Trade Organization

(WTO) agreements contributed in an

extensive form to creation of the

garment industry in Bangladesh through

proposed elimination of trade quotas

by 2005, which took a significant

place with the Bangladeshi garment

owners to create more businesses in

the country (Cheek & Moore, 2003).

The ready-made garment industry in

Bangladesh has survived amid phasing

out of Multi-Fibre Agreement in 2005,

the entry of China into the (WTO),

and the increased competition from

other countries. In addition to free

trade zones, other forces that facilitate

globalization include reduced labour

and production costs in underdeveloped

countries (Friedman, 2007). The research

has found that in the process of internationalization

of production, many companies and

nations have moved their manufacturing

operations to developing nations to

enjoy the privileges of cheap labour

and other facilities like - non-trade

union activities, low regulation in

employment relations and many more

(Rahman, 2006).

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Bangladesh's

garment industry was well positioned

to take advantage of an abundant supply

of domestic cheap labour. Absenteeism

of cheap labor was a comparative advantage

and a vital tool in the development

of the Bangladesh garment industry

throughout that entire period. The

introduction of the Multi-fibre Arrangement

(MFA) in 1973 also played a very important

role which is pondered by many as

the key factor in Bangladesh gaining

RMG market (Rahman, 2006). The rapid

growth of the readymade garments industry

in Bangladesh has been facilitated

by the following factors as well which

are: cheap labour; lack of employment

options for women; simple technology;

small amount of capital required;

and economic changes and policies

that encouraged the growth of this

particular industry (Khosla 2009;

Haider, 2006). These factors are inter-related.

The relatively cheap cost of labour

in Bangladesh is the reason for its

comparative advantage internationally

since goods can be produced at a lower

cost in Bangladesh than in many other

countries. This cheap cost of labour

is in turn a result of national policies,

massive unemployment and the willingness

of women to work for low wages (Khosla,

2009). Khosla (2009) identified through

her investigation that women's relative

lack of marketable skills and education

makes garment work highly attractive

to them. Combined with the high supply

of labour relative to the jobs and

the rising demand for dowries garment

work is highly sought after.

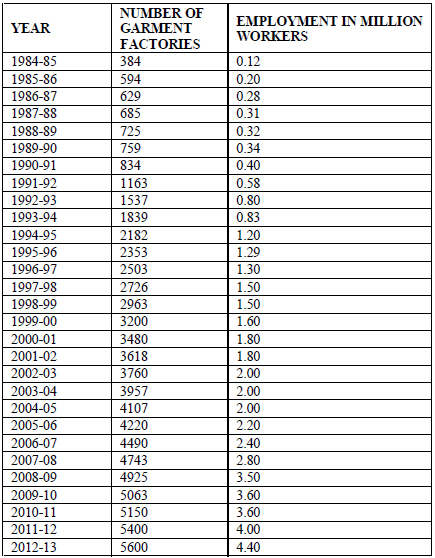

Below Table 2 shows the trend of

total workers being deployed since

1984 to 2013

Trade Information

Table 2:

MEMBERSHIP AND EMPLOYMENT

Source: BGMEA

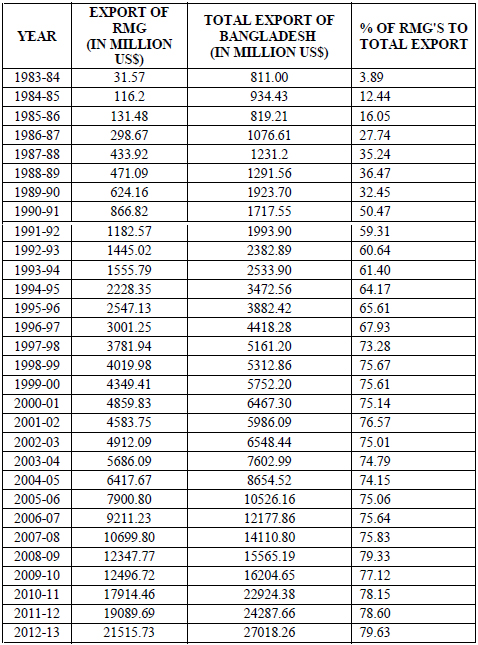

Below Table 3 shows the trend of total

export value from 1983 to 2013

Table 3:

COMPARATIVE STATEMENT ON EXPORT

OF RMG AND TOTAL EXPORT OF BANGLADESH

Data Source Export Promotion Bureau

Compiled by BGMEA

2.5 Garment industry in Bangladesh:

era of globalization and neoliberalization

"To analyze world politics in

the 1990s is to discuss international

institutions: the rules that govern

elements of world politics and the

organizations that help implement

those rules"

Keohane (cited in Chorev, 2005)

Chorev (2005) saw a significant role

of the WTO in the process of trade

liberalization. Indeed WTO made effusive

changes among the world organizations

that can play the indispensable role

over national and international political

economy in the current process of

globalization. To analyze the notion

of "globalization", most

international scholars have most often

referred to the process of international

economic integration, while the organizational

dimensions were ignored under the

process of globalization (Chorev,

2005). Since the postwar period, international

organizations (IOs) tremendously increased

from 61 in 1940 to 231 by 2002. One

IO is the WTO. The organization officially

commenced on 1 January 1995 under

the Marrakesh Agreement, replacing

the General Agreement on Tariffs and

Trade (GATT), which commenced in 1948.

Many scholars asserted that the WTO

(vice versa of GATT) played a very

eminent role over forming the NAFTA

which ultimately led globalization

and neo-liberalization in this globe

(See Chorev, 2005; Munck, 2010; Harvey,

2005).

Following diplomatic negotiations

dating back to 1986 among the three

nations, the leaders met in San Antonio,

Texas, on December 17, 1992, to sign

NAFTA. With much consideration and

emotional discussion, the House of

Representatives approved NAFTA on

November 17, 1993, 234-200. Clinton

signed it into law on December 8,

1993; it went into effect on January

1, 1994. The vision and mission of

NAFTA was to create more jobs, and

unequivocally many international scholars

subsumed that the establishment of

the WTO marked a turning point in

the governance of trade under neo-liberal

globalism, from a "trade liberalization"

project, in which governments were

allowed to compensate those suffering

injuries due to the process of free

trade, to a "trade neo-liberalization"

project, but a scenario is totally

different in many developing nations

where multinational corporations doing

business and exploiting proletarians

extensively, and Bangladesh is the

current example of this process at

the moment (Ahamed, 2004; Mottaleb

& Sonobe, 2011; Majumder &

Begum, 2000; Rahman, 2004). In fact

from the very beginning the view of

globalization was seemed a political

project of establishing new institutional

arrangements both at the national

and international levels (Chorev,

2005).

Since the quota system was abolished,

many developing nations have tremendously

fallen into the pressure from neo-liberal

globalized trade system, and this

was more strong when China became

free from quota restrictions from

2009 towards access to the US markets

(Asuyama, et al. 2013). But fortunately,

due to huge low paid abundant female

workers, Bangladesh has received its

favorable treatment during the last

one decade or so (see Majumder &

Begum, 2000; Rahman, 2004; Haider,

2006). The forces of globalization

have sparked an ongoing debates between

developed and developing countries

regarding adherence to international

labour standards in international

trading agreements (Truscott, Brust

& Fesmire, 2007, p.1; Hoq, et

al. 2009).

Globalization has been playing an

important role in many developing

nations in changing its socio-economic

structure. In Bangladesh, the economy

moves from aid to trade. Bangladesh

became the 2nd largest apparel exporting

country in the world. During the fiscal

year 2010-2011 garment exports totalled

USD19.9 billion, a 43% increase over

the previous year. It enjoys zero

duty access in the European Union

where 60 percent of garment products

are exported along with Canada, Australia,

Japan, Norway and Switzerland through

the GSP scheme (BGMEA, 2013). In the

global trade system, a garment could

be designed in New York, made of fabric

woven in China, spread and cut, and

sewn in Bangladesh, and marketed in

Australia. This is the chain of global

trade and Bangladesh enjoying its

positive outcomes at every stage of

transactions with the modern and developed

countries (Cheek & Moore, 2003).

The sweatshop: a movable system in

the global order. The sweatshop requires

little capital, basic technology and

cheap labor for formation (Bender

& Greenwald, 2003, p.7). In the

1980s and 1990s, economic globalization

leveraged by advancements of technology

led to the creation of more multinational

companies (Cheek & Moore, 2003).

Contemporary observers also understand

the sweatshop as transnational. The

contracting and subcontracting system

that was once limited to a single

nation or, more likely a single city,

is now global (Bender & Greenwald,

2003, p.7). NAFTA and WTO agreements

contributed to increased globalization

(Cheek & Moore, 2003; WTO, 2012).

To establish a global labour market

the mobility of labour is not necessary

since the price of labour is shaped

via the global market prices of goods

- the lower labour costs in developing

countries play a significant role.

They exert ever greater pressure on

the wages in developed countries.

The allocation of labour is achieved

by the mobility of capital, which

flows towards the basins of cheaper

labour taking productivity levels

into account. The situation has worsened

in the last decade when capital in

the developed countries has found

investments in industry and new jobs

uninteresting and reverted to financialisation.

Globalization in the developed countries

has thus turned into an outflow of

investment capital and jobs, the stagnation

of wages and living standards of masses

of workers, restrictions on social

security and welfare systems, the

rising indebtedness of individuals,

companies and states, and unemployment

tremendously high.

Studying the Bangladeshi sweatshop

means examining many paradoxes. The

economic roots of the sweatshop are

international, but its effort is national,

Bender and Greenwald (2003, p.7),

and Bangladesh, from a very early

stage of its process, extensively

exploited its cheap labour and capitalists

took other advantages over the country's

week labour laws and regulations.

Critically, in the context of economic

globalization, theorization around

the state involves assessments of

its weakness or continued strength,

of state incapacity given the strength

the global capital or its capacity

to act with impunity (Connor &

Haines, 2013). If we consider the

theory of economic globalization and

its effects on developing countries,

undoubtedly it reflects the consequences

nations are facing at this moment

in the post economic global trade

relationship between developed nations

and developing nations. Bangladesh

is not an exception in these dilemmas,

which we can easily identify in the

country's garment industry. The researchers

presently predict and confirm through

their vigorous investigation in this

regard that sweetshop and its activity

will never be vanished, but it can

be regulated (Bender & Greenwald,

2003, p.10). So what at present in

Bangladesh is very much needed to

keep this sector under a smooth condition

to save its positive progress at present

and in the future?

3. Working conditions

and minimum wages in the garment industry

in Bangladesh in the era of free trade

and neo-liberal globalization and

the ILO's obligation

Many international scholars raised

their concern over working conditions

and minimum wages for workers in the

garment industry in Bangladesh. In

fact, this news was unearthed to the

public, NGOs, advocacy groups, international

trade union forums, international

buyers, both locally and internationally.

To break up this postulate, so far

very limited work has been done in

this sector that I found in the literature

review (see Cheek & Moore, 2003;

Rahman, 2006; Ahmed, 2004; Mahmud,

2008; Majumder & Begum, 2000;

Mottaleb & Sonobe, 2011; Islam

& McPhail, 2011). Working conditions

in the Ready Made Garments (RMG) sector

is vulnerable and do not often maintain

international standards. Islam and

McPhail (2011) found a similar notion

as I found in my research.

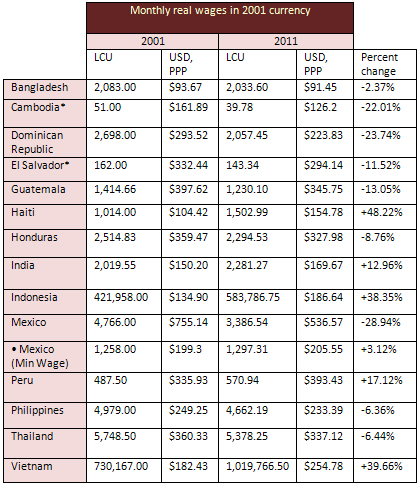

A short list of ten countries, in

5 of the top 10 apparel-exporting

countries to the United States-Bangladesh,

Mexico, Honduras, Cambodia, and El

Salvador-wages for garment workers

declined in real terms between 2001

and 2011 by an average of 14.6 percent

on a per country basis. This means

that the gap between prevailing wages

and living wages actually grew.

Table 4: A list of monthly wages

in 15 of the top 21 apparel exporters

to the United States, in 2001 currency

Source: Global Wage Trends for Apparel

Workers, 2001-2011, Worker Rights

Consortium July 2013 - Centre for

American Progress

From Table 4 we can get a clear picture

of real wages for the garment workers

in Bangladesh, which are even below

the living cost. It should not be

forgotten that neo-liberalized free-trade

globalization movement was created

for more capital mobilization towards

creating more jobs, but indeed, it

has created more jobs in this globe,

especially in the South, however it

has drastically ruined workers harmony

and suppressed workers' individual

and state's productivity on a robust

scale. Unfortunately world giant retailers

remain unrepentant when they were

required to take proper initiative

in this turmoil. Recent analysis says,

Wal-Mart refused to sign on the accord

that is requiring factory compliance.

Hensler (2013) an American Judge,

prepared a report atop global wage

trends for apparel workers, 2001-2011,

which was held in July, 2013 and known

as Worker Rights Consortium, where

he addresses very interesting things

with research findings and other data

over a period of time between 2001-2013,

in which it clearly reveals that the

garment workers' real wages dramatically

declined in that period, but living

costs and other liabilities increased

unexpectedly.

Mr. Hensler also showed in his report

that Bangladesh and Cambodia, the

fourth-and eighth-largest clothing

exporters to the United States in

2011, respectively, dramatically expanded

their apparel exports to the United

States during this period but concurrently

workers' real wages waned by -2.37%,

which is unjustifiable to any degrees.

According to Cheek and Moore (2003),

The United States are made by the

nation's 10 largest retailers. The

world's largest retailer, Wal-Mart,

alone generated revenues of $166 billion

in 1999 and almost $400 billion in

2013, an amount more substantial than

the economics of 100 countries, including

Portugal and Ireland (Cheek &

Moore, 2003). This company has been

identified as one of the retailers

in the world, which company immensely

exploits apparel workers in this globe,

especially in Bangladesh, and an example

has already been mentioned in the

preceding discussion.

Astonishingly we observed that big

international retail companies, never

intended to take any major initiative

to minimize this un-equilibrium trend

in the real wages system in the garment

industry in Bangladesh to demystify

such notion being originated to the

critics. Nevertheless the ILO declared

in their fundamental constituents

that workers should not be treated

as a commodity, but it is truly known

to everyone at present that workers

are not only treated as a commodity,

but also treated as an easy source

of making huge profits by exploiting

them to many degrees (see Hensler,

2013; Ahamed, 2013; Islam and McPhail,

2011; Rock; 2003). A tumultuous situation

is being observed by the author in

the garment sector in Bangladesh where

he identified many shoddy problems

occurring in the period of globalization

during the last three decades or so.

The paragraph below discusses and

shows a few examples of current upheavals

in the garment industry in Bangladesh.

Ullah (2014) identified Rana Plaza,

April 24, 2013 (1135 garment workers

lost their lives and approximately

3000 people were injured as the building

owner did not follow the correct building

code, also factory owners had forced

the sweat-workers to move in the building,

though the building was identified

just days before of the incident as

a shoddy building); Tazreen Fashions

(117 workers were killed); Spectrum

Garments (64 workers were killed and

80 others injured in 2005 - the illegally

built extra floors within the building

collapsed) and many more uncounted

workers lost lives in the past decades

since the country started producing

the garment products, and the workers

were brought up in a completely different

atmospheres than a compliant milieu.

Not maintaining international labour

standards and working conditions are

a clear violation of the ILO conventions

that we all see from our closest observation,

and international media and advocacy

groups and local and international

NGOs are urging for change in the

labour conditions along with some

other fundamental changes in this

sector, but the question is why the

ILO has failed to take its correct

and innovative strategy to demote

the number of accidents in the garment

industry in Bangladesh till today

(see, Cheek & Moore 2003; Rahman,

2006; Helfer, 2006; Ahmed 2004; Mahmud

2008; Majumder & Begum, 2000;

ABC, 2013)?

The ILO was established in 1919 and

became the first specialized agency

of the UN in 1946 that we identified

by analyzing some international scholar's

written documents Rodgers, et al.

(2009); Helfer, (2006); Hughes, (2005);

Henry, (2009), however, in our analysis

it unequivocally identified too that

the ILO is a very specialized organization

advocated by the UN for its blatant

work tenet which underpins the tripartite

program by adhering equal opportunity

in the dialectical conversation towards

better management in the work place

(Hughes, 2005). Determining the treatment

of workers' rights in the globalized

economy is a conflictive process (Douglas,

Ferguson & Klett, 2004). It has

widespread conflicted arguments among

multinational corporations, local

business enterprises, labour movements,

and human rights NGOs, in the global

North and global South, for carrying

different values and interest in regard

to workers' rights. In these social

conflicts the (ILO) has demonstrated

a magnificent concept among all as

a valuable means for conflict management

(See, Douglas, Ferguson & Klett,

2004). The ILO is known as a specialist

agency of the United Nations (UN)

whose mandate is the protection of

working people and the promotion of

their human and labour rights (See

Hughes, 2005; Henry, 2009; Rodgers,

et al. 2009; Helfer, 2006). In recent

years, the "ILO" has received

great attention in the public debates

about its triumph atop social injustice

and infringement in the work place.

In this debate, the ILO subsumed and

gyrated to demystify the concept as

unavailing in many facets.

The ILO sought to make a social balance

since its foundation in 1919, and

the preceding history of ILO is glorious

in the wake-up call for changing the

labour laws and other social inequalities

within the member states. But, notwithstanding

this is not the reality, in fact many

international scholars are howling

over the workers' rights and questioning

the ILO to justify their position

over many problems encountering workers'

socio-economic life and adhering with

more uncertainty (Helfer, 2006).

Bangladesh has been an active member

state of the ILO since 22 June 1972

and has ratified 33 ILO Conventions

including seven fundamental conventions.

The ILO opened its office in Dhaka,

Bangladesh on 25 June 1973, and initially

started working on expanding income-earning

opportunities through labour-based

infrastructure development and maintenance.

Bangladesh is the signatory of the

ILO and ratified eight fundamental

conventions by this time, but most

of them are not yet being implemented,

hence working conditions are not getting

changed since the garment industry

started their operation locally. But

the question is: why has the ILO failed

to obtain a remarkable result in this

sector since many years back though

they are trying onerously to save

the garment industry's reputation

from its moribund situation, but nevertheless

how strong aspiration do they have

- this is a good question indeed?

When the ILO faces its limitations

over enforcement power, other state

government get influenced to avoid

the ILO conventions that they ratified

already which we saw in Bangladesh

and in many other nations (see Helfer,

2006).

4. Findings

"Capital is dead labour,

that, vampire-like, only lives by

sucking living labour, and lives more,

the more labour it sucks"

- Karl Marx, (Capital, Volume 1, Chapter

10).

The above quote by Marx perhaps aptly

defines the condition of Bangladesh's

key export division and major foreign

exchange earner industry - The Garments

Industry. Marx characterized Globalization

as Universalization of Capitalism.

Globalization has often assumed a

direct, unmediated, causal link between

global economic pressures and the

formation of new policies. In this

process, the state flagrantly faces

a deleterious situation in most cases

as developing nations have less integration

power over state economic policy,

and state ignores the possible effect

on state institutions that we see

occurring in the garment industry

in Bangladesh. However, developing

nations can unitedly face this problem

if problems are encountering the states'

prosperity. Developed countries that

exploit labour should require provision

of minimum wages and sufficient technical

assistance to improve working conditions

of the workers, in which process they

can improve their living standard

as well. If the countries do not do

that of course consumers of these

countries can boycott their products

and raise their voice against capital

manipulation.

It has been profoundly found that,

the U.S. is the major player of the

sweatshop industry in this globe.

Relatively high wages, unionized northeast

to the low-wage, nonunionized south

in the 1920s and 1930s, the United

States apparel manufacturers have

for a long time relocated production

in search of cheap labour (Bonacich

& Appelbaum, 2003 p.142). However,

the most careful observations are

of the opinion that the first major

step towards the implementation with

the policy of the movement offshore

did not begin, more or less, until

well after World War II, (Bonacich

& Appelbaum 2003, p.142). The

development of expansion of offshore

sourcing began in 1956 with a vision

of producing low cost shirts "for

the people who live between New York

City to Los Angeles", sourcing

in Japan (Bonacich & Appelbaum,

2003, p.142).

Notwithstanding many international

researchers and scholars assume that

sub-Saharan Africa now to be given

special and favourable treatment,

such as duty-free and quota-free access

to the US. Market provided by the

African Growth and Opportunity Act

(AGOA), have been a real concern for

Bangladesh and other developing nation

who are producing garment products

for the US Market (see Mottaleb &

Sonobe, 2011). If the situation is

like that, of course a dynamic and

timely strategic model should be implemented

to keep this sector under smooth management

for the greater interest of millions

of livelihoods who are directly involved

with this industry, and the national

economy also belongs to this sector

on a robust scale.

As described by Waltman (2008), the

characteristics of the "New Liberalism"

of the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries was a conscious reaction

against mid-Victorian libertarianism.

The shift to new version of liberalism

is descried by him in his book in

which he argues that: "New Liberalism

is the next step in this evolution:

the notion that, in order for a society

to be maintained and to evolve, it

is necessary to take into account

our responsibility to future generations.

The key challenges of our time, from

climate change to the growing debt

and deficits, and the growing inequalities

all threaten not only our freedom,

but the freedom of future generations.

Where classical liberalism was centered

on negative freedom (freedom from

harm), and social liberalism was centered

on the broader concept of positive

freedom (freedom to develop), new

liberalism adds a further dimension

with the concept of timeless freedom

(ensuring the freedom of future generations

through proactive action taken today).

And if this is the case, indeed we

have to act right now to protect workers'

rights with more realistic observation

against the current global political

agenda that undoubtedly affecting

poor workers and subverting their

human rights at the very eminent scale.

The consequences have not examined

the fatal disaster of the Spectrum

Garments. Almost a decade after Spectrum,

buildings in Bangladesh remained structurally

unsafe: buildings are illegally converted

into factories and factories run day

and night in order to meet production

targets. Keeping costs low is prioritized

while widespread fatal health and

safety faults remain. Faulty electrical

circuits, unstable buildings, inadequate

escape routes and unsafe equipment

are a major cause of death and injury

(a complete violation of the ILO conventions

where Bangladesh is signatory) and

(a complete violation of social justice).

Working conditions are scant and it

often does not maintain international

standards, which is a prime concern

for the retailers and anti-sweat shop

campaigners. So the question is: How

can the Bangladesh garment sector

be better regulated?

References

ABC. (2013). Garment factory fire

kills in Bangladesh, ABC report, Dhaka,

Bangladesh

January 26, 2013 (AP).

Ahamed, F. (2013). Could monitoring

and surveillance be useful to establish

social compliance in the ready-made

garment (RMG) industry of Bangladesh?

International Journal of Management

and Business Studies, Vol. 3 (3),

pp. 088-100.

Asuyama, Y., Chhun, D., Fukunishi,

T., Neou, S., Yamagata, T. (2013).

Firm dynamics in the Cambodian garment

industry: firm turnover, productivity

growth and wage profile under trade

liberalization. Journal of the Asia

Pacific Economy, Vol. 18, No. 1, 51-70.

Balnave, N., Brown, J., Maconachie,

G., & Stone, R. (2009). Employment

relations in Australia, 2nd edn, John

Wiley & Sons, Australia Ltd.

Banglapedia. (2013). History of Bengal

Textile Industry. Accessed on 12 April

2013

BBC. (2013). Bangladesh garment collapse

(television documentary) (London:

British Broadcasting Corporation).

Bender, E. D., & Greenwald, R.

A. (2003). Sweatshop USA: the American

sweatshop in historical and global

perspective, Routledge, New York,

NY 10001

Beresford, M. (2009). The Cambodian

clothing industry in the post-MFA

environment: a review of developments.

Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy,

Vol. 14, No. 4, 366-388.

Bonacich, E., & Appelbaum, R.

P. (2003). Sweatshop USA: the American

sweatshop in historical and global

perspective, Routledge, New York,

NY 10001

BGMEA, (2014). Trade information.

http://www.bgmea.com.bd/home/pages/TradeInformation#.U4fOTPmSzys

Cheek, W. K., & Cynthia, E. M.

(2003). Apparel sweatshops at home

and abroad: Global and ethical issues.

Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences,

95(1), 9-19.

Chorev, N. (2005). The institutional

project of neo-liberal globalism:

the case of the WTO. Theory and Society,

34, pp. 317-355.

Connor, T., Haines, F. (2013). Networked

regulation as a solution to human

rights abuse in global supply chains?

The case of trade union rights violations

by Indonesian sports shoe manufacturers.

Theoretical Criminology, 17(2) pp.

197-214

Douglas, WA., Ferguson, JP., Klett,

E (2004). An effective confluence

of forces in support of workers' rights;

ILO standards, US trade laws, unions,

and NGOs, Human Rights Quarterly,

Vol. 26., pp. 273-299.

D'Souza, A. (2010). Moving towards

decent work for domestic workers:

an overview of the ILO's work. http://

www.ilo.org/publns / decent work/

domestic work /domestic worker/workers

rights/role of ILO 13.01.1 - ISBN

978-92-2-122051-0 (web pdf)

Garwood, S. (2011). Advocacy across

borders: NGOs, anti-sweatshop activism

and the global garment industry, Kumarian

Press, 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling,

VA 20166 USA.

Haider, M. Z. (2006). "Export

performance of Bangladesh textile

and garment industry in major international

markets", The Keizai Gaku Annual

Report of the Economic Society, vol.

68, No. 1 (Sendai-shi, Japan, Tohoku

University).

Helfer, Laurance R. (2006). Understanding

change in international organizations:

globalization and innovation in the

ILO, Vanderbilt Law Review, 59 Vand.

L. Rev. 649.

Henry, C.D. (ed.) (2009). Rules of

the game: a brief introduction to

international labour standards. ISBN

978-92-2-122183-8 (web pdf)

Henry, C.D. (2011). The committee

on the application of standards of

the international labour conference:

a dynamic and impact build on decades

of dialogue and persuasion / International

Labour Office - Geneva: ILO

Hensler, B. (2013). Global wage trends

for apparel workers: worker rights

consortium. Centre for American Progress.

http://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/RealWageStudy-3.pdf

Hoq, Z.M., Amin, M., Chodhury, A.I.

& Ali, S. (2009). The effect of

globalization, labor flexibilization

and national industrial relations

system on human resource management.

International Business Research, Vol.

2, No. 4.

Hughes, S. (2005). The International

Labour Organisation, New Political

Economy, Vol. 10, No. 3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13563460500204324

(Accessed on: 30 March 2014)

Islam, M.A., McPhail, K. (2011). Regulating

for corporate human rights abuses:

the emergence of corporate reporting

on the ILO's human rights standards

within the global garment manufacturing

and retail industry. Critical Perspectives

on Accounting,No. 22, pp. 790-810.

Khosla, N. (2009). The ready-made

garments industry in Bangladesh: a

means to reducing gender-based social

exclusion of women, Journal of International

Women's Studies. (MLA 7th Edition).

Mainuddin, K. (2000). Case of the

Garment Industry of Dhaka, Bangladesh,

Urban and Local Government Background

Series, No. 6 (Washington, D.C., World

Bank).

Majumder, P. P., & Begum, A. (2000).

The gender imbalance in the export

oriented garment industry in Bangladesh:

policy research report on gender and

development, working paper series

no 12.

Marx, K. (1956). Capital. Volume 1,

Chapter 10. Progress Publishers, Moscow,

USSR.

Mosoetsa, S., Williams, M. (2012).

Labour in the global South: challenges

and alternatives for workers, International

Labour Office - Geneva: ILO

Munck, Ronaldo P. (2010) "Globalization

and the labour movement: challenges

and responses," Global Labour

Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 2, p. 218-232.

Mottaleb, K.A., Sonobe, T. (2011).

An inquiry into the rapid growth of

the garment industry in Bangladesh.

Economic Development and Cultural

Change

Available at: http://digitalcommons.mcmaster.ca/globallabour/vol1/iss2/1

Rodgers, G., Lee, E., Swepston, L.,

& Daele, J.V. (2009). The International

Labour Organization and the quest

for social justice, 1919-2009 International

Labour Office, CH-1211, Geneva 22,

Switzerland. Available at: http://www.ilo.org/publns

Rahman, S. (2004). Global shift: Bangladesh

garment industry in perspective. Asian

Affairs, Vol. 26, N. 1, pp. 75-91.

Rahman, S. (2006). Is the high road

strategy enough: vulnerability of

the garment industry in Bangladesh,

Labour and Management in Development

Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3.

Rock, M. (2010). Labour conditions

in the export-oriented garment industry

in Bangladesh. South Asia: Journal

of South Asian Studies, n.s., Vol.

XXXVI, NO. 3.

Ross, A. (2003). Sweatshop USA: the

American sweatshop in historical and

global perspective, Routledge, New

York, NY 10001

Truscott, M. H., Brust, J. P., &

Fesmire, J. M. (2007). Core international

labor standards and the world trade

organization, The Journal of Business

Cases and Applications, pp. 1-5

Tsang, W.Y., Au, K.F. (2008). Textile

and clothing exports of selected South

and Southeast Asian countries. Journal

of Fashion Marketing and Management,

Vol. 12 No. 4, pp. 565-578.

Ullah, A.ASM. (2014). Legacy of Rana

Plaza: has social justice being established

in Bangladesh? Suprovat Sydney, http://suprovatsydney.com.au/legacy-of-rana-plaza-has-social-justice-being-established-in-bangladeshb-p695-1.htm

Waltman, J. (2008). Minimum wage policy

in Great Britain and the United States.

Algora Publishing, printed in the

United States.

Waring, P., & Burgess, J. (2011).

Continuity and change in the Australian

minimum wage setting system: the legacy

of the Commission, Journal of Industrial

Relations, Vol. 53, No. 5, pp.681-697.

WTO. (2012). Bangladesh Report on

Trade Policy. June 2012.

Zedillo, E., & Mahmud, W. (2008).

The future of globalization: explorations

in light of recent turbulence, Bangladesh:

development outcomes and challenges

in the context of globalization, Routledge,

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY10016.

|