|

Applying the Expectancy Theory to

Explain the Motivation of Public Sector

Employees in Jordan

Mira Nimri

Aya Bdair

Hamzeh Al Bitar

Department of Business Administration,

King Talal Faculty of Business and

Technology,

Princess Sumaya University for Technology,

Amman, Jordan

Abstract

The purpose of this research is to

examine the motivation of public sector

employees in Jordan. A modified model

of Vroom's expectancy theory, which

includes five components: expectancy,

extrinsic instrumentality, intrinsic

instrumentality, extrinsic valence,

and intrinsic valence is adopted and

applied to 258 employees of 13 public

sector institutions in Amman. It remains

to be seen in what extent do intrinsic

and extrinsic factors motivate employees

and how should managers incorporate

strategies in order to make sure that

the rewards are answered with increased

productivity.

Introduction

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has

been facing a number of serious problems.

Since its independence in 1946, it

has suffered from several wars, a

lack of natural resources, and multiple

refugee crises. The recent turbulences

that resulted from the Arab spring

have also had a great economic impact

on the country, such as an overload

of refugee capacity and a negative

effect on tourism. Unfortunately,

all these problems that hindered progress

and development could not be controlled.

However, one of the main problems

that impact the country is one that

is fully within control yet seems

impossible to solve, that is, public

sector performance. Standing at a

rate of over 40% of total employment

with approximately 225,000 employees,

it is clear that one of the first

noticeable problems is over-hiring

with continuous decline in the quality

of services. This causes a long list

of serious problems affecting government

performance.

In an effort to reduce unemployment,

which as of mid-2014 stands at 12%,

the government employed 12,000 people

annually during the past few years.

This has led to serious problems of

burdening the government financially

as well as increasing the gap between

employees' knowledge and the skills

required for their jobs, all in all

leading to decreased productivity.

There have been

serious efforts to improve performance:

through civil service system reforms,

increasing motivation with awards

such as the King Abdullah II award

for excellence in government performance

and transparency (initiated ten years

ago) and International Organization

for Standardization (ISO), which hopes

to also boost creativity in the public

sector, an element that is severely

lacking. However, there's still not

enough improvement.

Although progress has been witnessed

in certain departments, such as Drivers

and Vehicle Licensing Department,

and the Department of Civil Status,

most ministries and public sector

institutions are still suffering from

low quality services and administrative

flabbiness. The civil service system's

latest reforms should in theory motivate

employees to perform better. Among

the reforms made, there have been

several that addressed rewards for

performance.

Such a reform was an amendment to

article 76 which used to limit the

number of times an employee could

be upgraded based on merit removed

the limit, which should increase performance

and competitiveness. It is worth mentioning

that merit upgrading is based on the

employee's annual evaluation for the

last 5 years (last 2 years: Excellent,

the 3 years before: Very good) and

a clean record (no disciplinary action

taken against him/her).

Another important amendment is that

now employment is by contracts, thus

lowering the feeling of absolute job

security that makes some employees

less productive. Now an employee has

to uphold a certain level of performance

to ensure he or she is not fired.

An amendment that truly addresses

the personal and professional development

of the employees is an amendment which

states that any employee that acquires

a new educational qualification (for

example: a bachelor's degree) will

receive an increase in annual bonuses.

Other changes that in general aspire

to improve overall performance and

human resource practice include downgrading

the penalties so they start with a

warning instead of a direct deduction

from the annual bonus; this aims to

genuinely control and improve employee

behavior instead of immediately penalizing

them. They also expanded the authority

of the secretary general of each institution

to include addressing and adjusting

the conditions of the institution's

staff, changed the name of the employee

committee to the human resources committee

and added to its attributes human

resource planning and management.

In addition to that, they canceled

the bonuses committee and added its

tasks to the human resource committee.

And in an effort to control the bloated

government they set the maximum number

of supporting jobs at 30% of total

jobs.

It is clear that the civil service

system does have rewards for those

that work hard and perform well. That

has been the case even before the

newest reforms, yet that does not

show in performance. So it is necessary

to see how employees perceive these

rewards to understand where their

motivation stems from. Another important

factor to consider is the personal

motivation of public sector employees,

and how they see their own personal

and professional development in their

public sector careers.

It is essential to understand how

the employees perceive their work

and the rewards they receive for it.

One theory that could explain this

is the Expectancy Theory (Vroom, 1964).

The expectancy theory explains how

the motivation force is formed by

examining the employees' perception

on three levels:

1. Expectancy, which

addresses how employees see the effort

they put into their job affects their

performance.

2. Instrumentality, which explains

how employees view potential rewards

for their performance.

3. Valence, which shows the

value employees place on those rewards.

Since there is huge concern over public

sector performance and its negative

impact on the country, it is critical

to examine the problem with a scientific

approach. There are many elements

in the complex equation to enhance

performance and productivity, and

in this research we choose to focus

on only one: public sector employee

motivation.

Literature Review

Vroom's expectancy theory of motivation

(1964) attempts to explain the reason

behind employees' motivation through

understanding the perception the effort

put into work to the reward they receive

in return. It is composed of three

factors, as follows:

Motivation force = Expectancy x Instrumentality

x Valence (i.e. VIE model)

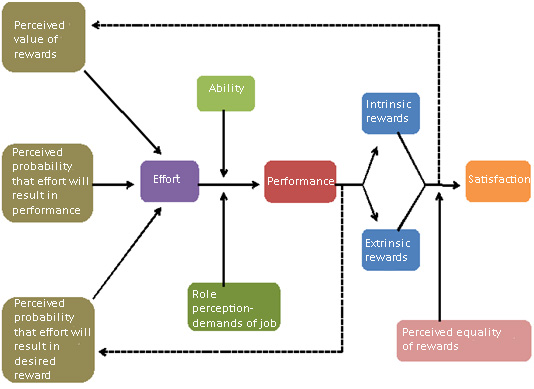

The expectancy theory suggests that

employees will be motivated to work

harder if they believe their effort

will result in good performance, and

that performance will lead to a reward,

and that reward will satisfy a need

worth the effort (See figure 1). Each

of those beliefs is represented by

a factor:

Expectancy: refers to an employee's

perception of the effort's role in

improving performance. This is determined

by self-efficacy, goal difficulty,

and perceived control. Self-efficacy

is an employee's self-assessment of

their capability to perform a task,

goal difficulty affects the employee's

perception of the attainability of

the goal (the more difficult a goal,

the less the expectancy), and the

perceived control of the job which

leads to an employee's development

of ownership and responsibility thus

leading to higher motivation.

Instrumentality: refers to

an employee's belief that good performance

will lead to a reward (could be tangible

or intangible). It is composed of

three variables, trust, control, and

policies; trust in who decides the

reward and it's receiver, control

of the decision making process in

case there is no trust, and policies

that clearly state how performance

will lead to reward.

Valence: The value of the reward

in the eyes of the employee. This

is determined by the needs, goals,

values, preferences, and sources of

motivation of the employee.

Based on a combination of all three

factors, employees will choose the

behavior alternative that gives them

the highest motivation force. The

higher each factor, the higher the

motivation. So, the theory is dependent

on perception; perception of effort

and performance, and performance and

reward, as well as the perception

of the value of the reward. Therefore,

the expectancy theory could be considered

a "process theory" (Fudge

and Schlacter, 1999) as opposed to

a content theory, since it depicts

how expectations lead to one behavior

or another depending on the individual's

perceptions.

Figure 1: Vroom's Expectancy Theory

Model

Criticism of the Expectancy Theory

Despite its popularity and general

acceptability, the expectancy theory

has not had enough empirical evidence

to validate it. It has been criticized

by many scholars; however the criticism

has not been a full rejection of the

theory, rather an extension to make

up for its weaker points. This has

led to various developments of the

theory by several researches who integrated

other elements into the equation.

The first generation of critics included

Graen (1969), Lawler (1971), and Lawler

and Porter (1967). Their main concern

was that the theory was too simple.

They did not believe it could accurately

predict an employee's increased effort

as a response to a reward. For example,

the reward might be a promotion, but

if that means more working hours,

then the employee might not place

high value on it, and so will not

put more effort. Lawler and Porter

also presented a modified version

of the theory to include extrinsic

and intrinsic factors (see Figure

1).

Landy & Becker (1990) suggested

that the key to improving the predictions

of the expectancy model might lie

in variables such as the number of

outcomes, valence of outcomes, and

the particular dependent variable

chosen for study.

Schwab (1979) examined the relationship

between the VIE model and two criterion

variables, effort and performance.

They included several moderators of

this relationship in 32 between-subject

studies in a statistical analysis.

Van Eerde & Thierry (1996) used

meta-analysis to examine the theory's

factors and their relationship to

five types of criterion variables:

performance, effort, intention, preference,

and choice. Campbell & Pritchard

(1976) argued that these set of variables

are too complex and poorly misunderstood

to be encompassed by a simple equation.

Starke & Behling (1975) did not

find that people made decisions related

to work effort in a manner consistent

with the axioms underlying the expectancy

theory: independence and transitivity.

To sum up, research has found that

the expectancy theory has proved its

worth, however not without an overwhelming

percentage of modified forms of the

theory. (Lawler, 1973)

Figure 2: Lawler and Porter's modified

expectancy theory, 1967

Motivation in the Public Sector

(Extrinsic/Intrinsic)

The research on motivation of public

sector employees has been growing

steadily for the past 40 years, yet

continues to severely lack consistency.

The general conclusion is that employees

are motivated through extrinsic rewards

(rewards provided by others such as

salaries, promotions), intrinsic rewards

(rewards that stem from the individual

such as satisfaction, feeling of accomplishment),

and public sector motivation (feeling

of responsibility and duty towards

the society). However, whether public

sector employees are more influenced

by one kind of reward or another is

still unknown. The debate has not

been conclusive, since many studies

are suggesting one configuration and

others are contradicting it completely.

Extrinsic rewards

Research regarding the extrinsic reward

of job security and promotion has

not been consistent. The research

ranged from evidence claiming public

sector employees value job security

less than the private sector employees

(Crewson, 1997) to other evidence

suggesting they value it more (Baldwin,

1987), to finding no difference between

the two sectors (Wittmer, 1991; Gabris

& Simo, 1995). As for promotion

of status and prestige, some research

found that it is less important for

employees of the public sector (Crewson,

1997), while other research found

there's no difference when they compared

the two studies (Wittmer, 1991; Gabris

& Simo, 1995).

Intrinsic rewards

The same contradictions have been

found in research on intrinsic rewards.

While it's been found that public

sector employees valued the feeling

of accomplishment and self-worth more

than private sector employees (Crewson,

1997), it's also been concluded that

they are not motivated by responsibility

and self-development (Buelens &

Van den Broeck, 2007). Another research

found that public-sector employees

don't place as much value on autonomy

and ability to work independently

as those in the private sector. A

more recent research found that there's

no specific difference across sectors

regarding having an interesting job

as a motivator (Houston, 2011).

Public Service Motivation

Public Service Motivation (PSM) is

a concept developed by Perry &

Wise (1990). Perry's research concluded

that public service employees, in

contrast to their private sector counterparts,

are motivated by their civic duty

and responsibility.

There is a lot of empirical evidence

to support Perry's statement, suggesting

that public employees are less motivated

by extrinsic rewards than the private

sector employees (Solomon, 1986; Wittmer,

1991). The presence of PSM and its

value for public sector employees

is also evident from research that

suggests employees of the public sector

are more willing to volunteer and

donate blood than the private sector

employees (Houston, 2006).

Further discussion on extrinsic/intrinsic

work motivation in the public sector

There is an overwhelming general belief

that public sector employees are motivated

intrinsically than extrinsically,

however research has mainly focused

on PSM as a representation of intrinsic

rewards. Because of this, the intrinsic

rewards of self-accomplishment and

self-worth, work independence and

autonomy, and self-development have

been somehow neglected in the literature.

Studies examining the pay-for-performance

and other financial incentives and

rewards concluded a "crowding

out effect", that is extrinsic

rewards actually decrease intrinsic

(PSM) motivation (Frey, 1994).

Other research simply points out to

the individual differences. Delfgaauw

& Dur (2008) suggest that public

sector employees could be divided

into three categories: lazy, regular,

and dedicated. Lazy employees avoid

putting effort into their jobs; dedicated

employees are motivated by PSM, while

regular employees are the same as

the dedicated ones but without the

PSM. Each category of employees has

different motivations, especially

when taking into consideration if

the effort is verifiable or not. Delfgaauw

& Dur (2008) found that lazy employees

prefer jobs where effort is unverifiable,

while on the opposite, dedicated employees

prefer effort that is verifiable.

Research has found that in countries

facing economic challenges and high

rates of unemployment, the public

sector is preferred as it provides

job security and stability (Boudarbat,

2008; Groeneveld et al., 2009). It's

also been found that the higher the

wages paid by the public sector, the

more the job attractiveness increases

(Adamchik & Bedi, 2000; Tansel,

2005).

Countries that have a career-based

system provide better job security

than position-based ones. In a career-based

system, employees are expected to

work their entire lives in the public

sector, promotions and career advancements

are decided by the government and

the labor market is internal. Whereas

position-based relies more on competence

regardless of their existence inside

or outside the public-sector labor

market, that is they don't mind bringing

in external employees to switch and

start work in the public sector (Hammerschmid

et al., 2007).

Research has found that the lower

the income, the higher the preference

for public sector work for its job

security. In opposite to income, research

found that the higher the educational

lever, the less the preference for

public sector. As for age, older people

have been found to prefer public-sector

work more than younger generations

(Van de Walle, et.al, 2014).

Jordanian Public Sector Employees

While having public sector employees

rank intrinsic rewards higher than

extrinsic might seem like a good thing,

it might actually be a symptom of

a serious problem. If considered within

a Jordanian context, this could be

due to the fact that performance is

not directly related to an increase

in income or promotion. Employees

have very little trust that their

hard work would be rewarded. They

do not believe their original salary

is proportional to the work they do,

or that it is enough to satisfy their

needs. They also do not believe that

the promotion system is fair, or that

they would be rewarded financially

in any manner if they are more productive.

An even more serious problem is that

the same study also found that there

are overwhelmingly low moral incentives

as well. The employees do not believe

the government cares enough about

its employees' professional well-being;

the government does not provide medals,

honorary promotions, advantages for

participating in training courses,

participation in decision making,

transfer to another position for better

utilization of skills, and transfer

to a better department as a reward

for good performance.

However, in terms of the social incentives

provided by the government, the results

were significantly higher. Employees

found availability of a daycare center

and a room for prayer highly motivating.

Being provided with cultural services,

such as a cultural or sports center

as a reward for good performance,

lead to medium motivation, whereas

loans for social occasions, compensation

for transportation costs, and availability

of a cafeteria were found not to contribute

to motivation.

The study also found that the overall

performance of the employees is average.

The study looked at different aspects

of performance, such as: willingness

to work outside official work hours,

ability to solve work problems, ability

to act in critical situations, full

readiness to take responsibility,

commitment to work laws and procedures,

participation in management decision

making, possession of good communication

skills, constant performance improvement,

completing tasks according to the

required standards, and performing

work as effectively and efficiently

as required.

So, as concluded from the study, public

sector employees perceive social incentives

as their first motivator, followed

by moral ones, and finally financial

ones in Jordan.

Unfortunately, there has not been

sufficient literature regarding the

motivation of public sector employees.

Methodology

Our main goal is to address many

of the concerns stated in the previous

section in one holistic model. In

order to do that we adopted a research

design similar to that of Chiang and

Jang (2008). While their research

applies a revised model of the expectancy

theory to hotel employees, we want

to use it for the public sector employees

in Jordan. We believe that for the

particular contingency of the sector,

the model is also suitable for testing

their motivation.

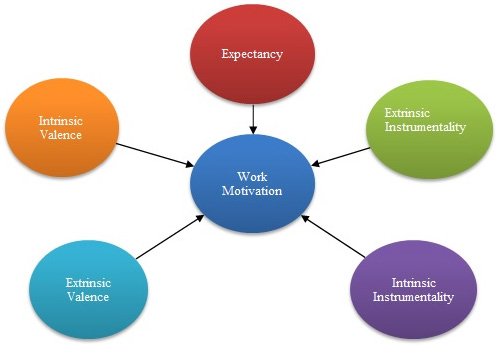

Chiang and Jang used an adjusted expectancy

theory model based on Porter and Lawler's

modified model (1973) (See Figure

3).

Figure 3: Chiang and Jang's modified

expectancy theory model, 2008

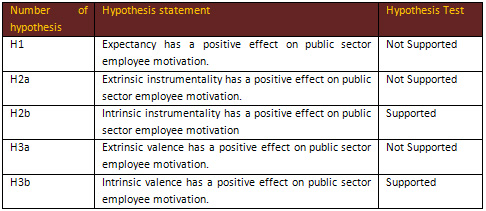

Research Hypotheses

The research proposes the following

hypotheses:

Expectancy (effort  performance):

performance):

If employees believe that putting

more effort into their job would lead

to better performance, then it is

logical to assume that in theory,

this perception would lead to increased

motivation. So we propose the first

hypothesis:

H1: Expectancy has a positive

effect on public sector employee motivation.

Extrinsic instrumentality (performance

extrinsic reward):

extrinsic reward):

If employees believe that better performance

would lead to a desired extrinsic

reward, (promotion, bonuses, and better

salary) then it is logical to assume

that in theory, this perception would

lead to increased motivation. So we

propose the second hypothesis:

H2a: Extrinsic instrumentality

has a positive effect on public sector

employee motivation.

Intrinsic instrumentality (performance

intrinsic reward):

intrinsic reward):

If employees believe that better performance

would lead to a desired intrinsic

reward (feeling of accomplishment,

more control over job, and more confidence),

then it is logical to assume that

in theory, this perception would lead

to increased motivation. So we propose

the third hypothesis:

H2b: Intrinsic instrumentality

has a positive effect on public sector

employee motivation.

Extrinsic valence (desired extrinsic

reward):

If employees place high value on a

desired extrinsic reward then it is

logical to assume that in theory,

this perception would lead to increased

motivation. So we propose the fourth

hypothesis:

H3a: Extrinsic valence has

a positive effect on public sector

employee motivation.

Intrinsic valence (desired intrinsic

reward):

If employees place high value on a

desired intrinsic reward then it is

logical to assume that in theory,

this perception would lead to increased

motivation. So we propose the fifth

and final hypothesis:

H3b: Intrinsic valence has

a positive effect on public sector

employee motivation.

Statistical methods used

For the purpose of descriptive and

statistical analysis required for

the research objectives, the following

statistical methods were used:

1. Frequency and percentages to describe

the characteristics of the sample.

2. The mean and standard deviation

3. Cronbach's Alpha to examine the

internal consistency estimate of reliability

of test results.

4. Pearson correlation coefficient

5. Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA).

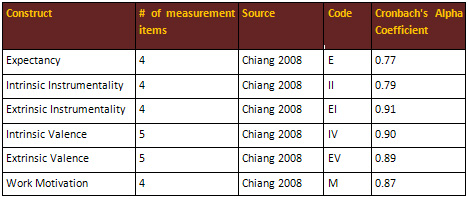

Variable construction

Theoretical: Referring to researches

(previous literature), official government

reports, and government civil service

system guide.

Practical: Distribution of

a questionnaire (Chiang, 2008) that

includes a section for each element

of the adjusted expectancy theory

model. (See Table 1)

Table 1: Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient

The research measurements were designed

using a 7-point Likert scale. The

Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient ranged

from (0.77 - 0.91) which is statistically

acceptable in managerial research

because it is larger than 0.75 (Nunnaly

& Bernstein, 1994). This indicates

that the measurements have internal

consistency.

Data Analysis

The methods of data collection and

statistical approaches used to analyze

the data are clarified in this section.

Descriptive analytical research methods

are used to analyze the collected

data due to the study questions, which

is to examine the 5 constructs of

the expectancy theory (expectancy,

extrinsic and intrinsic instrumentality,

and extrinsic and intrinsic valence)

and its relationship with employee

work competition.

The public sector in Jordan employs

approximately 225,000 employees. The

sample intended to represent a large

spectrum of employees, consisting

of 13 public sector institutions (The

Parliament, Ministry of Education,

Ministry of Interior, Ministry of

Environment, Ministry of Communication

and Information, Ministry of Planning

and International Cooperation, Natural

Resources Authority, Social Security

Corporation, Vocational Training Corporation,

Independent Commission for Elections,

Institution for Standards and Metrology,

Jordan Investment Board, Supreme Judge

Department, Health Insurance Department,

and Independent Election Commission).

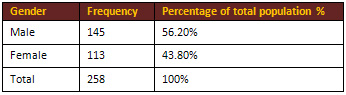

The population is composed by employees

in the Jordanian public sector. The

sample consisted of 13 institutions,

300 questionnaires were distributed,

282 returned, and 258 were suitable

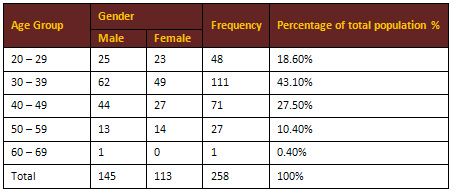

for data analysis. The gender ratio

was as follows: 56.2% consisted of

males and 43.8% of females. The age

of the sample ranged from 20 to 61

years old. The educational level variation

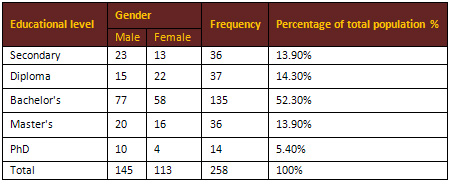

was as follows: 13.9% were at secondary

level, 14.3% held diploma, 52.3% Bachelors,

13.9% Master's, 5.4% PhD. (See Tables

2, 3, 4)

Table 2: Gender of the population

Table 3: Age group of the population

Table 4: Educational level of the

population

Results

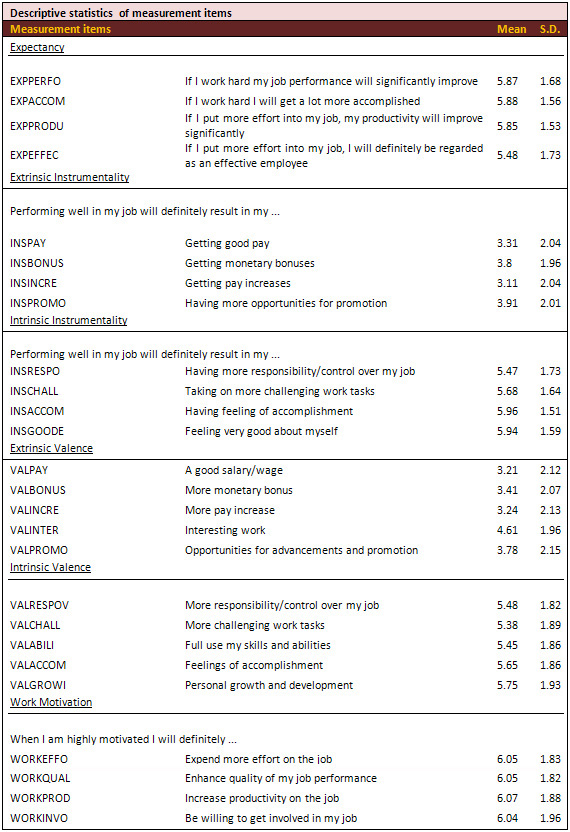

We concluded the extent to which

each measurement item was perceived

by employees through calculating their

mean scores, which are presented in

Table 5. For the expectancy's four

measures, the mean scores ranged from

5.48 (more effort leads to being regarded

as an effective employee) to 5.88

(working hard will get the employee

more accomplished) based on the 7-point

Likert scale. The extrinsic instrumentality

ranged from 3.11 (performing well

gets pay increase) to 3.91 (performing

well gets more opportunities for promotion).

Intrinsic instrumentality had noticeably

higher mean scores, ranging from 5.47

(performing well leads to more responsibility

or control over job) to 5.96 (performing

well leads to a feeling of accomplishment).

When it came to valence, the mean

scores were somewhat similar to instrumentality,

with extrinsic valence ranging from

3.21 (performing well leads to a good

salary), to 4.61 (performing well

leads to interesting work), and intrinsic

valence ranging from 5.38 (performing

well results in more challenging tasks)

to 5.75 (performing well leads to

personal growth and development).

Work motivation achieved high mean

score with the lowest being 6.05 (a

tie between high motivation leading

to expending more effort on the job

and enhancing quality of performance)

and the highest being 6.07 (high motivation

leads to increased productivity on

the job). So in conclusion, respondents

evaluated intrinsic instrumentality

as the highest. With the high mean

scores for work motivation, employees

indicated that high motivation would

lead to improved performance.

Table 5: Descriptive statistics

of measurement items

Note: A 7-point scale was used, from

1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly

agree).

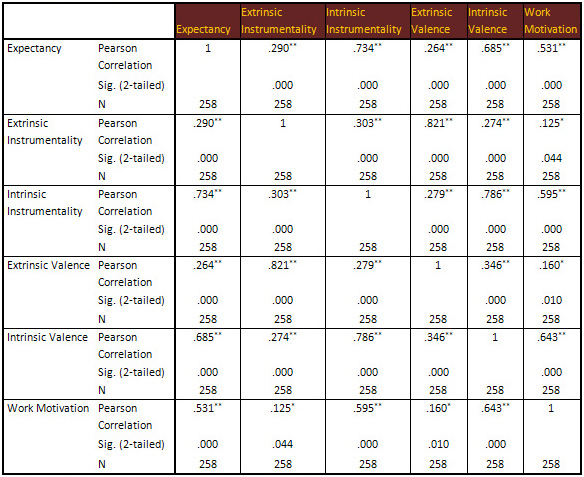

Table 6: Correlations

** Correlation is significant at the

0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Correlation is significant at the

0.05 level (2-tailed).

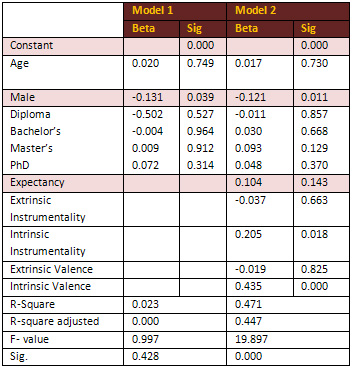

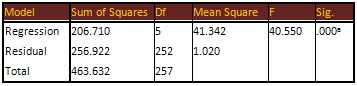

Table 7: Multiple Regression Analysis

The modified expectancy theory model

is validated as R-squared was able

to explain more the more than 47%

of the variance of the work motivation.

The F-value (approximately 19.9) proves

the fit of the model.

The analysis shows that extrinsic

instrumentality and valence do not

have a significant impact on work

motivation (the significance level

is above 0.10). However, it is interesting

to see that despite not being statistically

significant, the relation is expected

to be negative (the beta coefficient

is negative). So, Jordanian public

employees are actually less motivated

when they receive more extrinsic rewards.

However, this statement needs to be

further tested in future research,

since there is no statistical support

for it in our study.

The intrinsic instrumentality and

valence are statistically and positively

related to work motivation, with a

level of significance of 0.024 and

less than 0.001, respectively. The

biggest impact is assigned to intrinsic

valence. Results show that employees

are motivated with the reward of feeling

of accomplishment and personal growth

and development, so they place great

value on intrinsic rewards.

Expectancy is not statistically significant

(near 0.10 but over this threshold).

However, the expected relation should

also be positive in this case (See

Table 7).

Table 8: Results of the modified

expectancy theory model

Table 9: ANOVAb

a. Predictors: (Constant), Expectancy

Extrinsic Instrumentality, Intrinsic

Instrumentality, Extrinsic Valence,

Intrinsic Valence

b. Dependent Variable: Work motivation

Limitations

and Recommendations

We encountered some limitations while

collecting the data. The first one

is that the data was only collected

from public sector institutions in

Amman, which is the developed capital

of the country, so it might not be

representative of all employees across

Jordan. The data was only collected

from administrative staff, so it might

not be a fair representation of the

different types of public sector employees.

The data was sometimes collected with

the supervision of a manager, which

might have influenced the answers

of the employees.

We recommend public sector institutions

to look further into why extrinsic

rewards (even with the latest reforms)

do not resonate with the employees

as to better understand how employee

work motivation functions. In this

way, further improvements could be

made to the system.

Expectancy is not significant but

is very close to become so. This gives

hope that maybe with more improvements

in the public sector, expectancy could

increase leading to better motivation

and thus better performance. The public

sector job is very routine-oriented

with little room for creativity and

better performance. Decreasing, when

possible, the mundane tasks could

lead to improvements.

Conclusion

The validity of the modified expectancy

theory model is supported in this

study. The modified model explains

the expectancy, extrinsic and intrinsic

instrumentality, and extrinsic and

intrinsic valence of employee motivation

in the public sector in Jordan.

The research showed that the intrinsic

instrumentality and valence factors

have a significant and positive relation

with work motivation. This is good

news for the public sector, because

intrinsic rewards are easier to capitalize

on since they do not require financial

resources to incorporate into the

work environment. Therefore, it clear

that the management must recognize

intrinsic rewards and include them

in their human resource strategies

as they are important motivators for

the employees. The managers should

support and encourage a work environment

where performance is verbally recognized

and friendly competition is fostered.

Recognition of the employees' effort

and performance contributes to the

feeling of accomplishment and self-worth.

It is also good to care about their

employees' own personal growth and

development which can be done through

training, workshops, and helping the

employees obtain certificates that

qualify them for career advancements.

As for the extrinsic elements (instrumentality

and valence), they do not contribute

to work motivation as much as intrinsic

elements do. However, the public service

system does in fact reward performance:

annual evaluations are taken into

consideration in upgrades based on

merit, which should motivate employees

to improve performance. With the recent

reforms, there is no longer a limit

to the times an employee can be upgraded

based on merit. Another amendment

rewards employees with an annual bonus

if they acquire a new qualification

such as a bachelor or a master's degree.

Another one uses negative rewards.

Now employment is by contracts, which

means if performance does not reach

certain standards the employee could

have disciplinary actions taken against

him/her and even possibly being fired.

This should decrease the feeling of

job security that sometimes leads

to lack of productivity.

The research contributes to the existing

literature by being the first one

to implement the expectancy theory

in the public sector in Jordan, proving

its validity.

It also comes at an important time;

three months after the latest civil

service system reforms. The research

explains the employees' view of the

system after the amendments and their

impact on work motivation. Further

research could examine the motivation

of employees in response to the civil

service system reforms, to see if

they are having the desired impact.

Further research could also delve

into how employees are motivated by

intrinsic rewards and how that could

be incorporated into the everyday

work life in the public sector. Since

expectancy is very close to becoming

significant, future research should

look into how the public sector job

could be improved so that employees

are more motivated to be performant.

References

Adamchik, V. A., & Bedi, A. S.

(2000). Wage differentials between

the public and the private sectors:

Evidence from an economy in transition.

Labor economics, 7(2), 203-224.

Baldwin, J. N. (1987). Public versus

private: Not that different, not that

consequential. Public Personnel Management,

16, 181-191.

Boudarbat, B. & Chernoff, V. (2009).

The determinants of Education-Job

Match among Canadian University Graduates.

IZA Working paper No. 4513.

Buelens, M., & Van den Broeck,

H. (2007). An analysis of differences

in work motivation between public

and private sector organizations.

Public Administration Review, 67(1),

65-74.

Campbell, J. P. & Pritchard, R.

D. (1976). Motivation Theory in Industry

and Organizational Psychology, in

Dunnette, M. D. (ed.) Handbook of

Industrial and Organizational Psychology,

Chicago: Rand McNally.

Chiang, C. F., & Jang, S. (2008).

An expectancy theory model for hotel

employee motivation. International

Journal of Hospitality Management,

27(2), 313-322.

Crewson, P. E. (1997). Public-service

motivation: Building empirical evidence

of incidence and effect. Journal of

Public Administration Research and

Theory, 7(4), 499-518.

Delfgaauw, J. & Dur, R. (2008).

Incentives and Workers' Motivation

in the Public Sector. The Economic

Journal, 118, 171-191.

Fudge, R. S., & Schlacter, J.

L. (1999). Motivating employees to

act ethically: An expectancy theory

approach. Journal of Business Ethics,

18(3), 295-304.

Gabris, G. T. & Simo, G. (1995).

Public sector motivation as an independent

variable affecting career decisions.

Public Personnel Management, 24(1),

33-51.

Graen, G. (1969). Instrumentality

theory of work motivation: some experimental

results and suggested modifications.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 53,

1.

Groeneveld, S., Steijn, B., &

Van der Parre, P. (2009). Joining

the Dutch Civil Service: Influencing

motives in a changing economic context.

Public Management Review, 11(2), 173-189.

Hammerschmid, G., Meyer, R. E. &

Demmke, C. (2007). Public Administration

Modernization: Common Reform Trends

or Different Paths and National Understandings

in the EU Countries. In: K.Schedler

&I. Proeller, I. (eds) Cultural

Aspects of Public Management Reform,

Emerald Group Publishing Limited,

pp. 145-169.

Houston, D. J. (2011). Implications

of occupational locus and focus for

public service motivation: Attitudes

toward work motives across nations.

Public Administration Review, 71(5),

761-771.

Landy, F. J., & Becker, W. S.

(1990). Motivation theory reconsidered.

In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings

(Eds.), Work in organizations (pp.

1-38). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press

Lawler III, E. E., & Suttle, J.

L. (1973). Expectancy theory and job

behavior. Organizational Behavior

and Human Performance, 9(3), 482-503.

Lawler, E. E. (1971). Pay and organizational

effectiveness: A psychological view.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lawler, E. E., & Porter, L. W.

(1967). The effect of performance

on job satisfaction. Industrial relations:

A journal of Economy and Society,

7(1), 20-28.

Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990).

The motivational bases of public service.

Public Administration Review, 50(3),

367-373.

Schwab, D. P., Olian-Gottlieb, J.

D., & Heneman, H. G. (1979). Between-subjects

expectancy theory research: A statistical

review of studies predicting effort

and performance. Psychological Bulletin,

86(1), 139.

Solomon, E. E. (1986). Private and

public sector managers: An empirical

investigation of job characteristics

and organizational climate. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 247.

Starke, F. A., & Behling, O. (1975).

A test of two postulates underlying

expectancy theory. Academy of Management

Journal, 18(4), 703-714.

Tansel, A. (2005) "Public?private

employment choice, wage differentials,

and gender in Turkey", Economic

Development and Cultural Change, 53(2),

453-477.

Van Eerde, W., & Thierry, H. (1996).

Vroom's expectancy models and work-related

criteria: A meta-analysis. Journal

of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 575.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and Motivation.

New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Wittmer, D. (1991). Serving the people

or serving for pay: Reward preferences

among government, hybrid sector, and

business managers. Public Productivity

& Management Review, 369-383.

|