|

Overcoming

SMEs’ resistance to learning

through a metaphor/storyline approach:

A qualitative assessment of a novel

marketing intervention

Josef Cohen

Corresponding author:

Dr Josef Cohen

Derby University

United Kingdom

Email: sticks33@gmail.com

Abstract

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs)

have a high failure rate when compared

with larger firms, even when controlling

for the age of the business. This

is a problem because SMEs are important

for job creation and economic growth.

Instructor-led intervention strongly

predicts SME survival. Marketing is

one area in which intervention can

improve performance. However, to date,

few interventions exist to improve

marketing skills and strategy among

SMEs, and none have been subjected

to rigorous examination. Additionally,

interventions often face the problem

of resistance to learning among SME

managers and employees. The purpose

of this qualitative, phenomenological

study was to assess a short-term marketing

intervention with a metaphor/storyline

approach, to answer the following

research question: What is the meaning

of the intervention program for participants,

and how does the intervention change

SMEs’ organizational culture?

Pre- and post-intervention interviews,

along with a researcher’s log,

provided qualitative data for coding

analysis. Results revealed five categories

pertaining to the changes effected

by the intervention: (a) perceptions

of marketing, (b) organizational structure,

(c) organizational culture, (d) marketing

activities and sales, and (e) brand

awareness. It was concluded that the

intervention overcame resistance to

learning and resulted in some operational

changes at participating SMEs, but

lasting structural and cultural change

were minimal after the intervention.

Key words: SME marketing,

small business marketing, business

intervention, marketing intervention,

metaphor, storyline approach, training,

adult education

Please cite

this article as: Josef Cohen. Overcoming

SMEs’ resistance to learning

through a metaphor/storyline approach:

A qualitative assessment of a novel

marketing intervention. Middle East

Journal of Business. 2018; 13(1):

17-31 DOI: 10.5742/MEJB.2018.93184

Introduction

and Background

Small and

medium enterprises (SMEs) have a high

failure rate when compared with larger

firms (Alawa & Quisenberry, 2015;

Delmar & Shane, 2003, Storey,

Keasey, Watson, & Wynarczyk, 2016).

Firm size and probability of failure

are strongly inversely correlated,

even when controlling for the age

of the business (Haswell & Holmes,

1989; Purves, Niblock, & Sloan,

2016). Such high SME failure rates

are a problem because SMEs are important

to job creation and economic growth

(Gilmore et al., 2001; Jones &

Rowley, 2011; O’Dwyer et al.,

2009), and they thereby contribute

to the stability of national economies

(Maron & Lussier, 2014).

Instructor-led intervention strongly

predicts SME survival (Lussier &

Corman, 1995; Maron & Lussier,

2014). Therefore, it is important

to design interventions that can help

improve SME business success and reduce

the SME failure rate. Marketing is

one area in which intervention can

improve performance. In Israel, where

the present study takes place, 24%

of managers of failed SMEs claim that

their failure was due to their inability

to market strategically (Friedman,

2005). This was the top-cited failure

reason, with finance (20%) being the

second most common. Several studies

around the world have identified good

marketing as a key to SME business

success (Bates, 1990; Moutray, 2007;

Shane & Delmar, 2004), because

it helps SMEs remain competitive against

larger firms (Van Scheers, 2011).

Without marketing knowledge, SMEs

may experience difficulty remaining

solvent, and bad marketing may make

existing problems worse (Jovanov &

Stojanovski, 2012; Moutray, 2007).

Tock and Baharub (2010) indicated

a need for a facilitator-led intervention

that teaches SME managers and employees

to effectively implement marketing

to be competitive. However, few such

interventions have been developed,

and, to my knowledge, none have been

subjected to rigorous empirical examination.

This lack of research on marketing

interventions targeting SMEs is one

of the problems addressed in this

study.

Another key problem is that, in SME

contexts, there is often strong resistance

to learning on the part of managers

and employees (Furst & Cable,

2008; Frese et al., 2003; Legge et

al., 2007; Spangler et al., 2004).

There is a need for research examining

interventions with the potential to

overcome resistance to learning in

SME contexts. In my opinion, a different

paradigm is needed to address the

SME resistance to learning among SME

managers and employees and thus improve

their marketing knowledge, based on

existing literature related to SME

training needs. The purpose of this

qualitative study was to examine short-term,

facilitator-led intervention designed

to improve SMEs’ marketing skills

and strategies while avoiding resistance

to learning. This study was originally

part of a larger, mixed-method study,

the quantitative results of which

have been published elsewhere (Cohen,

2017).

Training Methods in SME Contexts

Research suggests that there are unique

requirements for successful training

programs in SME contexts (e.g., Wenger,

2000). Legge et al. (2007) explored

SME managers’ study method preferences

and found that managers tend to expect

quick, practical, and no-embellishments

training. According to Kuster and

Vila (2006), case analyses and lectures,

which are common training methods

in business, are not effective because

they lack connection to learners’

practical contexts. Similarly, Kerin

et al. (1987) recommended using practical

training for managers’ and employees’

marketing education. Raelin (1990)

found that training programs in the

field (as opposed to in the educational

system) should be tactical, focused,

practical, and effective. They should

also focus on implementing the material

in real life. Finally, Fraser et al.

(2007) claimed that, when conducting

a training program, collaborative,

interactional techniques are better

than lectures given to groups of workers.

Despite these findings suggesting

that the traditional lecture method

is not effective in the case of SME

managers and employees, Kuster and

Vila (2006) indicated that there is

a tendency among developers of employee

and manager marketing education to

rely on traditional methods of teaching.

Instead of traditional, instructor-led

strategies, organizational learning

programs should focus on active learning.

This establishes the need for a new

marketing training approach targeting

SMEs using active learning approaches.

Felder and Brent (2009) defined active

learning as “anything course-related

that all students in a class session

are called upon to do other than simply

watching, listening and taking notes”

(p. 2). Active learning is an important

programmatic approach for encouraging

and enhancing entrepreneurial learning

(Jones et al., 2014). This is especially

true in family-run SMEs (Lionzo &

Rossignoli, 2011) and for marketing

educators (Ramocki, 2007).

Theoretical Background

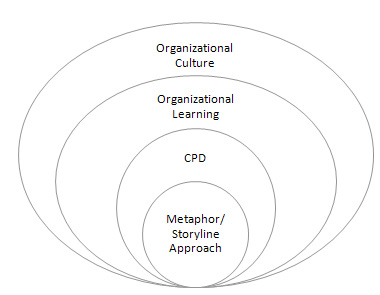

The practical, active training intervention

used in this study was developed following

a hierarchical, four-tier theoretical

framework. This framework has its

foundations in existing theoretical

and research literature related to

organizational behavior and SME marketing.

Each tier contains an important theoretical

concept that represents a specification

of the previous tier: organizational

culture, organizational learning,

continued professional development

(CPD), and metaphor/storyline training.

Figure 1 presents a schematic of the

theoretical framework, and the following

paragraphs describe the tiers and

their hierarchical structure in greater

detail.

Figure 1: Theoretical Framework

Organizational culture

The persistent lack of marketing

knowledge among SMEs can be identified

as a problem of organizational culture.

Schein (2011) defined organizational

culture as:

a pattern of shared basic assumptions

that a group learns as they solve

problems and situations of external

adaptation and internal integration,

which has worked effectively validating

its use and thus is suitable to be

taught to new members as the correct

way by which they should perceive,

think, and feel in relation to those

problems. (p. 241)

Organizations that do not regularly

implement marketing concepts and strategies

to solve problems and that do not

share marketing knowledge openly among

members suffer from organizational

cultures that are not supportive of

marketing. For this reason, organizational

culture is taken as the foundation

of the theoretical framework for the

intervention examined in this study.

Cultural factors play a key role in

determining organizational outcomes.

Organizational culture affects the

way employees behave in a company

(Moreland et al., 2013). Managers

use organizational culture to focus

their employees’ attention on

the company’s priorities and

to define how they want employees

to behave (Berson et al., 2007). Therefore,

organizational culture contributes

to a business’s success (Prajogo

& McDermott, 2011).

Organizational culture is closely

related to the extent of knowledge

sharing within the organization (Fox,

2004). Knowledge sharing helps employees

find important information easily

and quickly (Ismail Al-Alawi et al.,

2007). A culture that is not supportive

of knowledge sharing leads employees

to retain the knowledge they have,

so latent knowledge does not become

active within the organization, even

if that knowledge would better the

organization (Saint-Onge & Armstrong,

2012). It is therefore necessary for

the organization to set in place measures

that favor the sharing of knowledge

(Roberson et al., 2012), including

marketing knowledge, by establishing

an appropriate culture.

In many organizations, environments

of uncertainty, dynamism, and independence,

as well as a strong need for better

utilization of information and knowledge

systems, hinder performance (Bowling,

2007). The development of an organizational

culture that embraces knowledge sharing

remains instrumental in influencing

employee growth (Shafritz et al.,

2015). The intervention investigated

in this study emphasizes change from

closed cultures of independence to

open cultures of knowledge sharing.

Organizational learning

One way for an organization to enact

culture change and acquire knowledge

resources is via the organizational

learning process. Thus, the next tier

of the theoretical framework consists

of organizational learning. This process

is critical for the organization,

since it enables the organization

to adapt to its surroundings and to

maintain and even increase its competitiveness.

Thus, organizational learning contributes

to the survival or development of

the organization (Argote & Miron-Spektor,

2010; Cheng et al., 2016; High &

Pelling, 2003; Simsek & Heavey

2011; Trong Tuan, 2013). Organizational

learning is a relatively new concept;

in the past, there was a less dynamic

economy and a relatively slow adjustment

was required,

so there was no need for a concrete

theory of and approach to organizational

learning (Argote & Miron-Spektor,

2010; Dencker et al., 2009; Tyre &

Von Hippel, 1997).

According to Law and Chuah (2015),

there are two main definitions of

organizational learning. The first

is a knowledge-level definition, which

holds that organizational learning

occurs when “individuals acquire

new knowledge and incorporate it into

the workplace so that the collective

set can reach its shared visions”

(Law & Chuah, 2015, p. 10). The

second is a learning-level definition,

which focuses on different levels

of the organization at which learning

can occur. Although individuals are

the organization’s learning agents,

learning can occur at team and organizational

levels. In this view, the knowledge

acquired by individuals does not directly

influence the organization, but rather

shared knowledge and meanings constitute

changes that manifest at higher levels.

Organizational learning involves integration

of new and existing knowledge in the

daily conduct of the organization,

with the aim of improving employee

performance, outcomes, self-efficacy,

and openness to change (Bates &

Khasawneh, 2005; Castro & Neira,

2005). Existing employees may bring

knowledge with them, or knowledge

may be acquired through, for example,

training intervnetions. Each piece

of knowledge is acquired in a certain

context, which can be either active

or latent (Argole & Miron-Spektor,

2010). Latent knowledge has an effect

on the active context by means of

which the learning takes place. For

instance, a psychological environment

in which employees feel comfortable

with each other (latent context) affects

the learning capacity of the organization

(active context). Furthermore, the

accumulated knowledge is embedded

in the organizational context and

therefore alters the contexts through

which learning takes place (Coen &

Maritan, 2011).

Organizational learning is often beset

by resistance to change on the part

of employees and managers (Legge et

al., 2007). The organization is a

cooperative system that depends on

the willingness of its members to

support it. The participation of the

employees is particularly important

during periods of change, when the

organization is attempting to create

new types of situations that differ

from existing ones (Furst & Cable,

2008). Uniquely, SME managers, who

are often entrepreneurs who founded

the business, can also resist change,

thinking that they know everything

there is to know about their business

(Frese et al., 2003; Spangler et al.,

2004). Compounding this problem is

the fact that SMEs often do not have

the resources to hire highly knowledgeable

employees, so existing organizational

knowledge maybe be limited. Successful

interventions aiming at organizational

learning must therefore impart new

knowledge while addressing resistance

to change.

The intervention explored in this

study utilizes the principles of organizational

learning to provide the organization

with adaptive tools that will allow

it to better interact with the business

environment and, thus, better exploit

opportunities in the environment,

enhancing survival probabilities of

the organization. The intervention

takes the everyday experience of the

participants as a resource for discussion

of marketing issues; then, the intervention

changes the active knowledge of the

participants by introducing new knowledge

about the experiences discussed. In

addition, participants are encouraged

to try out their new knowledge when

confronted with actual encounters

with clients in their daily business

activities, and these experiences

are later discussed in the group to

foster more active content learning.

Continued professional development

Continued professional development

(CPD) is one path to sustained organizational

learning, and this concept forms the

third theoretical tier of the intervention

in this study. CPD is defined as a

process of lifelong learning for professionals,

with the following advantages: personal

development; assurance that professionals

are up-to-date, given the rapid pace

of technological advancement; assurance

for employers that their employees

are competent and adaptable; and development

of skills and knowledge (Fraser et

al., 2007).

Lydon and King (2009) found that successful

implementation of CPD programs is

explained by factors related to organizational

learning, such as classroom environment,

contents of the program, and teaching

method. The relevance and coherence

of the CPD program were also found

to contribute to CPD program’s

impact (Penuel et al., 2007). Successful

CPD enhances the ability of a firm

to adapt to its business environment.

This is true because CPD involves

learning and knowing more about the

market, market forces, competition,

and technologies. The result is that

a CPD program increases firm performance

and survival rates, as well as its

ability to innovate and lead the market

(Lenburg, 2005).

This traditional view of CPD emphasizes

the flow of knowledge from instructor

to student. More recently, a less

one-sided view of CPD has grown in

popularity. Fraser et al. (2007) recommended

interactive CPD programs that allow

the student to be an active and equal

partner in the learning process. Such

methods are believed to increase student

involvement in the learning process,

thus enhancing understanding, memorization,

and implementation of new knowledge

(Fraser et al., 2007).

The intervention examined in this

study adapts this strategy to the

SME marketing environment. CPD programs

are effective even when short in time

and number of sessions (Lydon &

King, 2009). Studies have shown that

most participants in short CPD programs

changed their professional behavior

after attending the programs, to a

moderate to significant extent. Short

CPD programs are necessary, as professionals

are not willing to take part in long

programs (Lydon & King, 2009).

Metaphor/storyline approach

The most specific level of the present

intervention’s theoretical framework

is the metaphor and storyline approach;

the CPD program uses this approach

to enhance participant learning. This

section describes how the metaphoric

storyline approach helps participants

make sense of marketing by expanding

the options for learning and understanding,

providing real world experience, and

overcoming resistance to learning.

A metaphor is figurative language

that links one specific object to

another by alternating various descriptions

of the objects. Figurative language

expresses something that, in everyday

life, denotes a connection to one

area while transferring that denotation

to another area, which is analogous

to the first (Bremer & Lee, 2007).

A metaphor has two parts: the topic

and the information that spurs the

metaphor (the vehicle). The topic

identifies what the metaphor is about,

and the vehicle is an analogy that

creates a link between the topic and

other global contexts. For example,

in the advertising sentence “Budweiser,

the King of Beers”, Budweiser

is the topic and the rest of the sentence

constitutes the vehicle (Bremer &

Lee, 2007).

Metaphors are used as part of marketing

and management educational programs

because they expand the options for

learning and understanding by encouraging

participants to expand their areas

of thinking. Metaphors enable participants

to consider broad ideas, rather than

specific, defined questions. In addition,

this way of thinking is suited to

how humans commonly think, which makes

studying via metaphors more natural

to many students (Fillis & Rentschler,

2008).

Another advantage of using metaphors

is that they are relevant for the

practical world, not just for academic

thinking, which makes the educational

program more accessible for participants.

This is an especially important condition

of success in business training (Kuster

& Vila, 2006). Finally, the use

of metaphors helps bridge the gap

between the concepts and academic

theories in the practical world of

management, increases the cooperation

and exchange of views between the

two worlds, and narrows the cultural

gap between them (Fillis & Rentschler,

2008).

Metaphors can be used in CPD programs

as a means of explaining complex concepts

and of breaking up these concepts

into simple ideas, which can be related

to on a practical level. Metaphor

is particularly appropriate to marketing,

since the use of metaphors is extensive

in everyday marketing, ranging from

the use of metaphors in publishing

to promote brands to strategic marketing

thinking, which includes concepts

that are all metaphorical, such as

the term ‘brand personality’

(Cornelissen, 2003; Durgee & Chen,

2006).

Mills (2008) showed that teaching

marketing ideas using metaphors can

be very effective. Mills found that

using metaphors from jazz, a type

of music, in the marketing world could

have a profound impact on the behavior

of participants in educational programs.

Mills (2008) claimed that using such

metaphors can teach participants knowledge

of marketing issues, giving them the

ability to creatively use that knowledge

in their everyday professional lives

and promoting leadership and confidence

(Mills, 2008).

In his definitive study, Mills (2008)

attempted to teach students strategic

thinking using metaphors from jazz,

whereby the instruments, skills, timing,

and rhythm were all analogous to marketing

situations. The students learned marketing

methods when they applied the jazz

metaphors to the field of marketing.

The study showed that students perceived

the lessons as very interesting, and

they saw how their skills in strategic

marketing thinking improved. The author

noted that the jazz metaphor facilitated

students’ understanding of marketing

concepts and marketing problems. In

addition, it activated creative thinking

with regard to possible solutions

to marketing problems. Mills (2008)

found that using metaphors not only

enhanced students’ ability to

act on their marketing knowledge,

but it also promoted creative listening

and increased collaboration among

organization members.

Storyline is a strategy of active

learning developed in Scotland (Solstad,

2009). Solstad (2009) showed the success

of the strategy with teachers and

students. The storyline approach was

designed and tested for classrooms,

not SME settings. To date, no other

research addresses the use of storyline

approach as a strategy for learning

in SMEs. Therefore, the present study

will be, to our knowledge, the first

to test the storyline approach in

a small business setting.

Research

Question and Objectives

This study

was guided by the following research

question: What is the meaning of the

intervention program for participants,

and how does the intervention change

SMEs’ organizational culture?

The objective of this study was to

understand participants’ subjective

perceptions of the intervention in

order to describe the organizational

change process resulting from the

intervention and determine whether

this novel form of intervention holds

promise for improving SMEs’ marketing

abilities. I accomplished this by

(a) conducting pre- and postintervention

semistructured interviews to explore

participants’ perceptions of

the intervention and generate rich

descriptions of the organizational

change process, and (b) taking researcher

notes during the process of the intervention

to understand the process of change

on a day-to-day basis.

Because this is a qualitative research

question, there are no formal hypotheses.

However, I supposed that the intervention

would change participants’ perceptions

of marketing, particularly with regard

to marketing processes. I also supposed

that the intervention would increase

the extent to which participants engaged

in collaborative efforts related to

marketing, including the development

of new marketing strategies and tactics.

Finally, I supposed that the intervention

would lead to personal empowerment,

new energy for marketing, and a renewed

belief in the SME organizations’

potential to advance in their respective

markets.

Materials and

Methods

To address the need for a novel approach

to marketing education and development

among SMEs, we conducted a qualitative,

phenomenological investigation of

a facilitator-led marketing intervention

designed to enhance marketing knowledge,

skills, and strategy among SME participants.

This section contains a description

of the intervention program, of the

setting and sample, and of the methods

of the study itself.

Intervention Program

The intervention program explored

in this study consists of four facilitator-led

sessions held onsite at SME locations.

Each session lasts 90 minutes and

is attended by all members of the

organization, including managers and

employees. During each session, the

facilitator presents part of a story

based on a metaphor. The storyline

connecting all four sessions involves

a castle in a large kingdom, with

three knights who must work together

using their strengths to attract villagers

to the castle and defend the castle

from attacks by neighboring castles.

Each session includes several developments

in the story arc, each of which connects

to a concrete marketing concept with

an expected learning outcome. After

hearing each story, group members

complete an individual assignment

reflecting on the content of the story.

The group is then asked to discuss

the story and reach a consensus decision,

with the help of the facilitator’s

mediation, about how the story should

progress. Next, the facilitator shares

the metaphoric connection between

the story and SME marketing concepts,

skills, or strategies. During this

stage, the facilitator emphasizes

how the group’s decisions could

be applied to marketing in the SME’s

real-world context. The group’s

decisions are connected to the following

session’s stories for continuity.

The intervention program avoids using

traditional methods of teaching. Instead,

it is based on play-like interaction,

using metaphors, between the moderator

of the intervention and the participants,

and does not relate to marketing issues

and concepts directly in an academic

tone, but rather compiles a storyline

with the participants that relates

to their everyday working experience

and imaginary themes, such as mediaeval

villages, knights, and kings. This

approach should allow the participants

to become involved in the process

of learning, retain interest in the

contents of the meeting, and practice

an effective learning process.

The issue of resistance to change

is addressed by relating to marketing

issues and ideas in a tangible rather

than threatening or boring way, thus

making the experience of learning

fun and empowering. The use of metaphors

in the intervention, which are used

to mask marketing theories learned

behind a fun metaphor simulation,

is designed to assuage fear of change

and of confronting academic knowledge.

Furthermore, since participants are

an integral part of an active learning

process, managers and staff need not

be threatened by the program and experience

changes they themselves make.

Setting

and Sample

The setting for this study consisted

of SMEs in Israel. Inclusion criteria

included:

1. The SME was active in Israel.

2. A minimum of four employees worked

directly for the SME.

3. A minimum monthly turnover was

NIS 30,000, VAT included.

4. The SME was not a non-profit organization.

5. The SME had been in operation for

less than 10 years.

After placing an advertisement and

contacting potential participants,

10 SMEs approached the researcher

in a period of one month. Three did

not qualify, and two stated that they

were too busy. Five qualified and

were interested in participating in

the study

If potential participants expressed

interest and were qualified, the researcher

conducted interviews with the managers

to further describe the study and

to establish their willingness to

cooperate. I informed them that, as

part of their participation in the

study, they would be administered

an intervention designed to improve

their marketing ability and business

outcomes. If, after this interview,

the SME owners were still interested

in participating, they provided consent

in writing. The SME owners were able

to withdraw from the study at any

time. All businesses participated

in the study of their own free will

and received no compensation for their

participation other than the intervention.

Table 1 (next page) details the characteristics

of the five SMEs included in the study.

Printing, five employees were excluded

because they did not have tenure and

did machinery-related work only. At

Telepele, one of the two investors

was not involved in the daily operations

of the business and was thus excluded.

The same was true of two investors

at Future Chair. Interneto had one

technical employee who just supported

the data with no involvement in the

daily operations and worked from home;

this employee was thus excluded. Food

for Thought had one employee who was

only 15 years old and was thus excluded.

This yielded a final sample size of

22 participants. The following paragraphs

describe each SME setting in more

detail.

Participant 1: ABC Printing. ABC

Printing had a staff of 10 employees

in a highly competitive market. The

owners and staff had no prior knowledge

in marketing and believed that only

the price will attract clients. The

existing marketing message was confused

(see Ries & Ries, 2009). Relations

with suppliers were positive, but

there was little ongoing contact with

a client base. Clients were for the

most part walk-ins, because of the

location of the business. Employees

appeared to be in low spirits and

expressed concern that the situation

in the organization might result in

closure. Participation in the intervention

was prompted by the fear that they

were about to go under. Communication

between the two owners, Suzan and

Mark, was far from ideal. They did

not share common core values or goals

and aspirations for the organization,

nor any articulated marketing strategy.

Participant 2: Telepele. Telepele

was a highly organized company. The

hierarchy and the distribution of

tasks were clear, regular meetings

were held with the staff and management,

and advertising and other marketing

operations were performed. However,

the unique voice of the SME was not

manifested in its marketing efforts,

nor was there a clear understanding

of the competitive advantages of the

company. The organization’s main

competitor was a large major leader

in the market, and the company tended

to copy aspects of the competitor’s

advertising campaigns. Telemarketing

operations were at the core of sales

generation. Management was disappointed

with the telemarketing department

and complained about results.

Participant 3: Food for Thought.

The owner of this organization had

no formal education in marketing or

business and operated based on intuition.

Allocation of resources was sporadic;

no clear marketing scheme was employed;

there was no website, no strategic

marketing look of the business, and

client development was poor. Core

values were vague, as was the corresponding

marketing and graphic language. Internal

communication at Food For Thought

was good; all those involved wanted

the business to succeed. Competition

by similar and larger companies was

strong.

Participant 4: Interneto. Interneto’s

financial state was poor, and the

CEO had a hard time envisioning a

brighter future for the company in

the competitive Israeli market. There

was disagreement between the two managers

(who are a father and son) about running

the business. The son had an education

in business and marketing, but found

it difficult to influence his father’s

views regarding management of the

company. Disagreements between the

two resulted in the absence of a clearly

articulated strategy for the company,

a common vision, or core values. Employees

worked from home. There was no organizational

identity, the website was not updated

regularly, and there was no means

of developing a strong client base.

The main stream of clients was generated

by advertisements, occasional mass

e-mail distributions, and word of

mouth. The general feeling of the

staff was negative.

Participant 5: Future Chair. The

organization was in the final stages

of developing its product. A sample

was available online and sales had

begun. However, money was fast running

out. Communication between the owner

and staff and between the CEO and

investors was good; all wanted the

business to work better. Nonetheless,

the business strategy was not clear

and this often resulted in disagreements.

The CEO had a formal education in

marketing; however, she found it hard

to influence investors’ views

on how to manage the SME and move

towards better marketing operations.

During the first year of this business,

no real business connections were

made; prospective clients showed little

interest in the product, and the existing

investors were losing interest in

the company. The investors took on

a private business consultant prior

to the intervention. The CEO was confused

and unsure of the future of the SME,

mainly in terms of growth, allocation

of funds, and investments. The website

was not updated regularly, and the

sales person had no training, no clear

sales goals and methods, nor a defined

budget.

Research Instrument

The research instruments consisted

of a semi-structured interview guide

and a researcher log.

Interview guide. I developed a pre-

and post-intervention semi-structured

interview guide with prepared questions

followed by probes, allowing participants

to express themselves at length on

focused topics (see Ardley, 2005).

Questions for the interview guide

were informed by existing literature

and by the aims of this research.

The interview guide was also designed

to create a relaxed, trusting atmosphere

(see Shkedi, 2003). Before and after

the intervention, interviews consisted

of the same set of 21 questions:

1. Please explain what marketing

means for you.

2. At present, in your opinion,

are the organization’s marketing

activities managed professionally?

Please explain.

3. At present, please spell

out the main marketing concept that

represents or unites the organization.

Do you think that the rest of the

organization’s workers would

agree with you?

4. How do you think your competitors,

suppliers, customers, colleagues,

family, perceive you (think about

you)? Please explain.

5. Please state your position in the

organization. In your opinion, is

your current position connected to

the marketing system? Please explain.

6. At present, do you have

a sense of confidence in the organization’s

marketing system? Please explain.

7. Do you feel that you can

initiate new elements and add to the

organization’s marketing system?

Please explain with regard to your

own position as well.

8. Please elucidate your organization’s

uniqueness versus the competition

in your field of activity.

9. At present, do you think

that the marketing messages are conveyed

sufficiently and efficiently?

10. In your opinion, will new

and returning customers come and buy

from the organization?

11. Please detail the following

dimensions with regard to most of

the services/products sold by the

organization: functionality, emotional

value, and image value.

12. Please state a few sentences

that recur among the organization’s

staff when encountering the organization’s

customers.

13. Please state your organization’s

unique colours and their significance

(or: why did you choose those colours

specifically).

14. Please state the organization’s

slogan and its meaning (or: why did

you choose this slogan).

15. Please list the regular

criteria through which your organization

is managed from an operative perspective.

16. Do you feel that the staff

meetings at the organization are exhaustive

and efficient from your perspective?

Please state the frequency of the

meetings.

17. Do you feel that focused

efforts are made to create positive

rumours for different audiences that

come into contact with the organization?

Please explain.

18. Do you feel that the advertising

spread of the organization is guided

by strategic thinking? Please explain.

19. In your opinion, is there

enough input for following different

trends in the target market, competitors,

legal changes etc.? Please explain.

20. In the case of developing

new services/products, in your opinion

is there planning aimed at development

guided by dimensions such as perceptions

of the organization, image values,

overall strategy and trends? Please

explain.

21. Please explain whether,

in your opinion, there is sufficient

activity in the field of marketing

for the organization.

Researcher log

In addition to the semistructured

interviews, I also kept a researcher

log to shed additional light on the

effects of the intervention. For each

research log entry, I recorded the

day and time, the content of the entry

(my observations of the training session),

an associative reflection, and an

inductive conclusion. This structure

helped me create a well-organized,

repeatable log (see Sabar, 2002) that

will help readers get a detailed and

better understanding of the research

process (see Lincoln & Guba, 1985)

and will lead to greater reliability

(see Shkedi, 2003).

Use of a research log acknowledges

that the researcher is not an outsider,

but rather is part of the happenings,

taking part in as well as interpreting

the phenomena for the reader, so he

can make sense of what took place

in the field (Sabar, 2002). This was

especially important in the present

study, since the researcher was also

the consultant delivering the intervention

to participants.

Drawbacks of researcher logs include

that the log may be biased and not

reliable (Fan et al., 2006), the researcher

may lack introspection abilities,

the researcher’s understanding

may not reflect the situation, and

participants may perform better when

they know they are being observed

(McCarney et al., 2007). I overcame

these obstacles by recording the log

discreetly and taking into account

differences in my observations and

participants’ feedback to identify

potential bias. In the current study,

this research tool was used to express

the researcher’s thoughts and

reflections on the intervention process.

Methods

Data for this qualitative, phenomenological

study were collected in four phases.

The first phase consisted of instrument

development and focus group review

of the research instruments. The second

phase consisted of pre-intervention

semi-structured interviews to evaluate

participants’ perceptions of

the marketing skills and abilities

at their organizations. The third

phase consisted of the delivery of

the intervention and data collection

via the researcher log. The fourth

phase consisted of a post-intervention

semi-structured interview.

Data collection

Semi-structured pre-intervention interviews

took place at the SME’s business

place, face-to-face, in a closed room

with just the participant and the

researcher. Interviews were held just

before the start of the first intervention

session. I asked for the participants’

permission to record the interviews

and transcribed them later, allowing

for accuracy, transparency, and flexibility

during the interview process. Participants

were made to feel comfortable and

able to respond honestly and fully

with guaranteed confidentiality in

comfortable, private settings. The

interviews took 15 minutes on average.

Post-intervention interviews were

conducted three months after the last

intervention session. This three-month

latency period gave time for the SMEs

to work and assimilate the intervention’s

teachings. Interviews were held either

face-to-face or via e-mail. The same

interview questions were used in both

interviews. The rationale for this

procedure was to compare participants’

responses to both qualitative and

quantitative questionnaires before

and after the intervention.

Data analysis. I used a multistage,

open coding approach to analyze qualitative

data for emergent themes (see Elo

& Kyngäs, 2008). To ensure

validity of qualitative data, I analyzed

all qualitative data as they came

in, rather than waiting until the

end of the study, to ensure that the

right data were being collected and

that the research question could be

answered. In addition, early analysis

of data is very helpful in identifying

patterns, or major themes in the data

(Sabar, 2002). I also validated qualitative

data by performing member checking,

whereby I showed the researcher’s

log and interview transcripts to participants

to check whether or not they agreed

with the interpretations of their

observed behaviors (see Hubarman &

Miles, 2002).

External validation, which is a separate

phase of the validation process in

qualitative research, occurs when

the data matches the theoretical sources

or other research data (Sabar, 2002).

This type of triangulation indicates

the robustness of the findings and

allows for generalization of findings.

To create naturalistic generalizability,

I went back and forth between deduction,

induction, and reflection during the

research process. This process was

documented in the researcher log.

Connections between findings and existing

theory are detailed in the Results

and Conclusions sections.

Qualitative data were divided into

primary and secondary datasets for

analysis. Primary data were directly

derived from informants, and secondary

data came from the researcher’s

log and the SMEs’ marketing materials.

For both primary and secondary data,

content analysis was used to create

themes that described the main issues

discussed by research participants.

Content analysis is a process of arranging

and structuring the data gathered

for interpretation and grasping its

meaning. I used a code system to create

categories, by which a number represented

each meaning category. Further, I

highlighted categories using a color-coding

scheme for easier analysis and mistake

avoidance.

There are two categories of content

analysis: structural analysis and

subject analysis (Shkedi, 2003). Structural

analysis highlights the relationships

between processes in the field, while

subject analysis emphasizes the descriptors

of the processes being studied, including

the participant’s feelings, beliefs,

and thoughts. In the current research,

the content analysis process combines

both methods (Coen & Maritan,

2011). It is worth mentioning that

this analysis is culturally dependent

(Shkedi, 2003), and therefore some

of the meaning of the content might

be lost in the translation of the

qualitative data from Hebrew (the

language in which the original data

was collected) into English (the language

of this report).

In the Results section, I demonstrate

the themes by quoting participants

directly. Quotations were chosen for

their ability to clarify the theme

in the participants’ words. When

choosing a quote, I followed the guidelines

that the quotes support the main idea

of the paragraph, be punchy and direct,

and come from a participant source.

Results

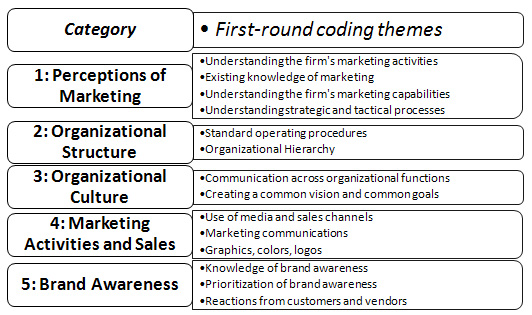

Figure 2 shows the five categories

that emerged from the data, as well

as the first-round codes that were

reduced into these final five. In

the following subsections, each category

is described in detail, with illustrative

excerpts from the interviews. Participant

names have been changed for anonymity.

Figure 2: Data Categories and Themes

Category 1: Perceptions of Marketing

Before the intervention, participant

organizations lacked an understanding

of the essence of marketing, the difference

between sales and marketing, and the

need for a marketing plan for the

business. Therefore, they made use

of tactical solutions for immediate

problems instead of constructing a

strategic business plan to guide their

way in managing the business’

survival and growth. The following

quotations illustrate this tendency:

Reliability and quality. What we

produce in this company, many companies

do. Besides reliability and quality,

I do not have anything to offer them.

And that is the problem here, that

all printing presses do the same thing…(Suzan,

ABC Printing)

Marketing is all about advertising.

(Dan, Food for Thought)

Because success was attributed to

advertising campaigns rather than

a marketing approach, the majority

of participants demonstrated little

knowledge of the factors contributing

to success in the companies they operated.

The following responses illustrate

participants’ responses to the

interview question, “In your

opinion, are your marketing activities

in the organization run in a professional

way?”

In my opinion, [activities] are

not conducted in a professional manner,

because we do not have any knowledge

about it. We do everything only according

to the knowledge we have. Like me,

for example, I market in an aggressive

way; I simply go to companies and

offer them what I have to sell.

(Joe, ABC Printing)

In my opinion, no, because there is

no marketing system. I do not know

if this is common in SMEs. We have

a marketing person, but he does not

only do marketing. He also works on

a commission basis. He is not enough,

that’s for sure. (Avivit,

Future Chair)

After participating in the intervention,

organization members knew more marketing

terms than before, were more aware

of marketing and its role in conducting

a business and of marketing issues

in managing a business, as well as

of how this new knowledge can help

them do better work in the everyday

conduct of the business. With respect

to marketing awareness, participants

were much more focused and were able

to give concrete and relevant examples

from their companies, contrary to

their preintervention responses. A

change in personal and operative marketing

approaches towards a more professional

way of using marketing tools was observed.

Before [the intervention] we had no

direction whatsoever. There was no

coordination, as if we were just shooting

in all directions, with no rules or

order. After the process, we were

much more focused and we chose customers

who were more suitable. That helped

us create markets for our product.

(Don, Future Chair)

Marketing is an integral part of

the organization, a way of life, in

your head all the time. It dictates

the way you work, it determines the

marketing language you use, and it

is a dominant factor in the life of

the business. You can definitely say

that we are always talking about knights.

(Dan, Food for Thought)

The marketing system works well

because it is also part of the job,

and it’s not just marketing per

se. For example, when our CEO talks

to customers, she also markets. The

marketing is ‘slipped in’

to the job. (Mark, ABC Printing)

Category 2: Organizational Structure

Although there appeared to be a general

understanding of the division of roles

in the organization, it was also the

case that, as relatively new SMEs,

workers tended to have more than one

role in the organization. As one respondent

put it, “My role in the organization

is ‘pach zevel’ (trash can—or

catch all)” (Sara, Food for Thought).

The same holds for definitions of

functions and operating procedures.

In response to the interview question,

“Could you specify criteria according

to which the organization operates?”

two referred to being on time as most

important. A few participants had

further remarks:

Actually, since the business is

mine and I am the CEO, all the marketing

falls to me. I am the one who decides

how to route, where to advertise,

and how much to invest in marketing,

and then it’s repeated all over

again. (Joe, ABC Printing)

You do it in the best way you can,

there’s no such thing as roles,

you work when you need to, and do

everything you can. I think that the

division of roles that we have built

up is still not clear. (Dor, Interneto)

During the intervention, the researcher

log indicated a change in thinking,

in which the division of roles in

the organization is connected to the

marketing dimension of the organizational

roles. It seemed that all members

of the group were involved in marketing,

came up with ideas, and seemed to

be more marketing oriented, even if

their job was not directly linked

to marketing (Researcher log entry).

Additionally, participants’ comments,

as noted in the researcher log, demonstrated

a process of increased understanding:

Dura: I can understand better how

to organize the marketing function

of the organization (Researcher log

entry)

After the intervention, interviews

revealed a sharpening of the functional

definition of the employees in the

organization, particularly those responsible

for marketing:

The organizational structure is more

organized, and my staff and I have

each been allotted our roles. This

means that everyone has his role defined,

which was not the case before. Before

this I felt that I had to do everything

and carry everything on my shoulders.

Today I spread it around a bit more.

(Sara, Food for Thought)

Yet, most of the organizations

did not implement significant structural

changes:

Change in the structure of the organization

has still not been implemented. There

is no change in the structure.

(Bob, ABC Printing)

I sensed no significant changes

in the level of the organizational

structure. Not something that I could

put my finger on. But I hope that

it will come. (Dean, Telepele)

It appears that the intervention did

not move the organization to make

any significant longitudinal structural

changes. At the same time, the conceptual

internalization helped the organizations

reformulate their goals and marketing

objectives, and consequently redefine

the responsibilities and authority

of the various functions. These changes

helped increase employees’ sense

of security and facilitated the delegation

of responsibilities, thus reducing

the pressure on the managers.

Category 3: Organizational Culture

Prior to the intervention, there

was reportedly little notion of the

organizational vision or goals, no

common language, and minimal communication

between different levels or functions

within the organization. Meetings

were held sporadically and with no

clear agenda or procedure.

There is no common marketing strategy…we

are all shooting small arrows in all

directions. (Dura, Future Chair)

After the intervention, respondents

reported a change in the situation,

towards a common language among organization

members, based on the “knights”

metaphor used in the intervention.

For example:

The concept of the ‘knights’

is a very strong thing for us, and

constantly arises when thinking about

advertising. We highlight it constantly.

(Dan, Food for Thought)

Before the process, the marketing

idea was not as clear to the staff

as it is today. In meetings that we

had, everyone saw things differently,

and we had no consensus, nor a clear

knowledge of our main goals. Today

we are more geared towards speaking

a common language than we were before.

(Dean, Telepele)

The intervention created a dialogue

here, a conversation, a discussion…about

where we’ve come from and where

we’re going, what is important

to us and what isn’t, what we

have to do, and how we see things.

Discussion was created here that wasn’t

there before. The words were translated

into actions, so actions came into

being. (Riki, Telepele)

The researcher log concludes that

the intervention seems to have created

a real cultural change among the organizations

in this study. For example:

The entire organization seems to be

able to communicate much easier: people

use the same terminology, are willing

to discuss difficult issues, and are

much more open with each other. (Researcher

log)

The conceptual internalization helped

the organizations communicate more

effectively, focus more on objectives,

and understand the unique operational

track of the organization.

Category 4: Marketing Activities

and Sales

Before the intervention, organizations

were not satisfied with their marketing

efforts:

Communication with our customers is

not good enough. Advertising and public

relations are not good enough.

(Gal, Interneto)

I am a little stuck, as I do not

know how to advertise our good products.

(Doron, Interneto)

Advertising is not sufficient as I

do not know where to advertise.

(Dudu, Food for Thought)

After the intervention, there was

evidence of increased marketing activities,

in both frontal and non-frontal (online)

areas, as well as increased sales:

I feel that there is a lot more

activity going on because of the proper

marketing procedures we learned. There

is movement, deals are being closed,

and I definitely think that when I

am facing a customer I know what to

talk about and how to talk. (Sara,

Food for Thought)

Our statistics on the website (which

was enhanced due to the process) show

that we have more entries, more people

staying on the site for longer, and

I think there was also an improvement

in the sales due to this process,

and, of course, the innovations…

I see that we sell more, the sales

graph has risen, there was a 30% growth

in the first month after the intervention,

and in the next month it could go

up another 30%. (Dor, Interneto)

From a visual standpoint, participants

had adopted the usual standards of

the industry in their graphic presence,

so that, in practice, instead of differentiation

and innovation, they demonstrated

conformism and colourlessness. For

example, the company that offers catering

services chose a black uniform typical

of many organizations involved in

food service, and their slogan was

“Catering and Event Production”.

The representatives of the company

were not aware that this message does

not indicate the uniqueness of the

organization versus competition in

the industry. During and after the

intervention, there was evidence of

operative changes in various organizations,

towards better branding of the firms:

The owners are happy to make big changes

in the company’s marketing scheme.

The logo will be changed, and the

website will be changed. (Researcher

log).

The CMO has started a process to change

the graphic design of the company.

This will include the website, brochures,

business cards etc. (Researcher log).

I would like to say that I am truly

in a different place today, my advertising

looks different, my ads are more dignified,

more professional, more appealing.

Now when I look back on my old ads,

they were really amateurish and unprofessional.

I really enjoyed all the meetings,

I personally had a lot of fun there,

and I really wanted to keep on going,

keep on being supported…

(Sara, Food for Thought)

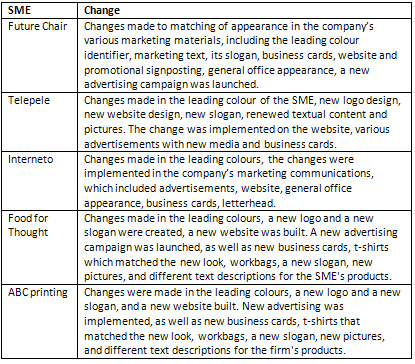

Due to ethical considerations, it

is not possible to present full documentation

of the physical changes carried out.

However, Table 6 illustrates that

changes occurred in the companies’

presentation, in a way that protects

the identity of research participants.

Post-intervention, there is some evidence

that the marketing changes were effective

from a sales standpoint:

I have already seen that the intervention

shaped our thinking and the message

we convey. A few customers have already

joined us because of the change. The

marketing mode is a lot more professional,

whereas before it consisted mainly

of just giving the price and that

was it. (Bob, ABC Printing)

The researcher log concluded that

marketing changes had been implemented

in all the organizations without exception.

In addition, the order and organization

that resulted from the intervention

allowed the SMEs to understand the

meaning, visibility, and marketing

concept of the organization on an

applied level.

Category 5: Brand Awareness

This category refers to how outsiders

view the company. Before the intervention,

the majority of respondents believed

that their company and they themselves

were viewed in a positive light by

trade partners. However, there was

also a consensus about the fact that

no positive efforts were being made

to present the company in a way that

would improve their reputations. Participants’

comments were generic:

I think that, on the whole, most

of them appreciate us, and we have

a relatively good reputation. (Gal,

Interneto)

I think that, all in all, the reviews

are good, professional, but there’s

still a lot more to be done. (Avivit,

Future Chair)

Postintervention, participants made

comments that were more practical:

I think the firm is a lot more

noticeable in terms of the customers.

There is a lot more interaction with

them. We improved communication with

the suppliers too, but it is more

in our interest to have better communication

with potential customers, less with

the suppliers. Our new way of communication

is mostly demonstrated in the language

we use, in what we offer, in how we

focus our core capabilities, and how

we want to bring it to the fore, to

the customer. (Suzan, ABC Printing)

Competitors, suppliers and customers

now think that we are a lot bigger

than we really are, and that we have

a reputation of being experts on the

subject. (Dor, Interneto)

However, the researcher log stated

that there appeared to be a discrepancy

between the improved awareness of

the subject and how little it was

implemented.

Table 2: Marketing activities

that changed following the intervention

Discussion

and Conclusions

This study was designed to answer

the research question: What is the

meaning of a metaphor/storyline-based

intervention program for participants,

and how does the intervention change

SMEs’ organizational culture?

The results indicated that the intervention

program had five effects, as evidenced

by the five qualitative main categories

that arose from the coding process.

Specifically, the intervention affected

participants’ (1) perceptions

of marketing, (2) organizational structure,

(3) organizational culture, (4) marketing

activities and sales, and (5) brand

awareness. This strongly supports

existing research showing that organizational

learning can lead to performance improvements

and competitive advantage (Argote

& Miron-Spektor, 2010; Castro

& Neira, 2005; Xenikou & Simosi,

2006). Moreover, theory suggests that

marketing that uniquely positions

the organization in the field will

enable increase in sales in the long

term (Ries & Ries, 2009).

Despite these positive results, the

effects of the intervention on organizational

structure and organizational culture

were not pronounced. Several participants

stated that they did not perceive

any changes in these areas. Therefore,

it can be concluded that the intervention

may not have a significant effect

on SMEs’ organizational culture.

This study revealed a weakness of

the intervention, which is the inability

to initiate a change of organizational

culture. This topic requires further

examination of short interventions

based on metaphor/storyline approaches.

Despite this weakness, the intervention

yielded practical, operational changes,

indicating its potential for improving

business outcomes through SME marketing

training.

Although results showed a noticeable

change in participant organizations

soon after the intervention, literature

suggests that no lasting change can

be made if the organizational culture

is not altered, and that only organizational

culture can make short-term achievements,

such as those gained from interventions,

into permanent changes (Dvir &

Oreg, 2007; Zhang, 2008). Schein (1990)

proposed that an organizational culture

is composed of three layers, and the

results of this study provide support

for the three-layer model. The intervention

appeared to initiate change in this

first layer, as indicated by participants

like Dan, who stated that the concept

of knights was used frequently in

his organization after the intervention

and enabled change to visible aspects

of the SME. Additionally, results

showed that participant organizations

held meetings more frequently and

discussed marketing issues more regularly.

However, it was less clear that these

changes penetrated to the second and

third layers of organizational culture.

These results support Schein’s

(1990) three-layer model of organizational

culture, since the divisions between

external, surface-level changes and

deeper changes to values and assumptions

were clearly visible. This interesting

finding suggests a need for interventions

that include long-term components

designed to take a systematic approach

to embedding external changes at deeper

levels, in accordance with the recommendations

of Dvir and Oreg (2007).

One of the key problems addressed

in this study was resistance to learning

on the part of SME managers and employees

(Fox, 2004; Copley, 2008; Devins &

Johnson, 2002; Kyriakidou & Maroudas,

2010). Learners may be impatient or

unwilling to take part in traditional

learning, expecting the learning process

to be short and yield immediate results

(Lydon & King, 2009; Zemke &

Zemke, 1984). The intervention tested

here appears useful for overcoming

this barrier. The intervention was

short and limited in time, and did

not use the traditional mode of lecture

teaching. Participants indicated that

they felt the intervention was fun,

which is another key to organizational

learning success (Mills, 2008). Additionally,

the intervention bridges the gap between

marketing theories and the real world,

and it generates solutions suited

to the real world, as recommended

by Fillis and Rentschler (2008). These

findings suggest that the characteristics

of the intervention may have overcome

barriers to organizational learning,

and other interventions using these

characteristics could be similarly

effective.

Zwan et al. (2009), asserted that

organizations need CPD in order to

survive. Results of this study support

that conclusion. Prior to participating

in the intervention, participants

indicated in interviews that their

survival was threatened by low earnings.

Postintervention, participants noted

an increase in sales and more positive

response from customers. The researcher’s

log confirmed this, observing that

participant organizations had more

sales leads than prior to the intervention.

This supports the notion that CPD

can lead to better business results

and that organizational learning that

improves SMEs’ organizational

performance is feasible (Zwan et al.,

2009).

The intervention program uses a narrative

storyline approach to convey marketing

concepts to the participants. This

approach is based on theoretical and

empirical foundation, indicating that

metaphoric language can be useful

in teaching new concepts to adults

(Bremer & Lee, 2007; Cornelissen,

2003; Durgee & Chen, 2006; Fillis

& Rentschler, 2008; Mills, 2008).

The results show that this approach

was indeed effective, as indicated

in the participants’ in-depth

interviews.

Future Research

The current study contributes to filling

a gap in the knowledge relating to

metaphor/storyline intervention for

improving marketing at SME businesses.

More studies are needed that focus

specifically on practical marketing

for SMEs. Further research will also

be required to better understand how

short organizational learning interventions

can translate to lasting organizational

culture change. Finally, this study

has only measured the outcome of the

intervention on the short term. More

research is needed to investigate

the long-term impact of the intervention

on marketing activities and business

outcomes.

Limitations

The research discussed here has a

number of limitations. First, as an

exploratory study, it was based on

a convenience sample. It is not unlikely,

therefore, that the sample is biased

in the sense that it included organizations

that a priori were seeking change.

This sampling method reduces the generalizability

of the findings. The small number

of individual participants also limits

generalizability. It is worth noting,

however, that such a sampling method

is very common in exploratory studies

and in qualitative research, and the

validity of qualitative data is judged

by its comprehensiveness and the depth

of the findings, rather than by its

manner of sampling.

A further limitation of the research

stems from the fact that the design

of the intervention program and its

evaluation were both carried out by

the same individual. Therefore, once

again, there is the possibility of

evaluating bias in the data and in

reported findings, caused by the emotional

and professional involvement of the

researcher with the research topic.

Relatedly, the small sample of participants

working directly with the researcher

during the intervention may have led

to social desirability bias in participants’

responses (Weisberg, 2005). Therefore,

the results should be interpreted

with care and confirmed in future

studies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the innovative approach

and methods of the intervention appear

to have been effective for those who

participated in the study. It united

participants around common marketing

goals, visions, and operative plans

for the organization. Although changes

at the organizational level appear

to have been more limited, it is also

the case that individual change is

a catalyst for organizational change

and growth (Prajogo & McDermott,

2011). Therefore, it can be concluded

that metaphor/storyline-based intervention

can be effective for improving SME

business success through improving

marketing skills and strategies.

References

Alaway, A., & Quisenberry, W.

(2015) ‘Understanding the factors

of small business failure in the Middle

East.’ Journal of Advanced Research

in Entrepreneurship, Innovation and

SMES Management, 2(2): 1-10.

Ardley, B. (2005) ‘Marketing

managers and their life world: Explorations

in strategic planning using the phenomenological

interview.’ The Marketing Review,

Vol. 5(2): 111-127. doi:10.1362/1469347054426195

Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E.

(2011) ‘Organizational learning:

From experience to knowledge.’

Organization Science, Vol. 22(5):

1123-1137. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0621

Bates, T. (1990) ‘Entrepreneur

human capital inputs and small business

longevity.’ The Review of Economics

and Statistics, Vol. 72(4): 551–559.

doi:10.2307/2109594

Bates, R., & Khasawneh, S. (2005)

‘Organizational learning culture,

learning transfer climate and perceived

innovation in Jordanian organizations.’

International Journal of Training

and Development, Vol. 9(2): 96-109.

doi:10.1111/j.1468-2419.2005.00224.x

Berson, Y., Oreg, S., & Dvir,

T. (2008) ‘CEO values, organizational

culture and firm outcomes.’ Journal

of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 29(5):

615-633. doi:10.1002/job.499

Bowling, N. A. (2007). Is the job

satisfaction–job performance

relationship spurious? A meta-analytic

examination. Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 71(2), 167-185.

Bremer, K., & Lee, M. (1997) ‘Metaphors

in marketing: Review and implications

for marketing.’ Advances in Consumer

Research, Vol. 24: 419-424.

Buchanan, J., & Evesson, J. (2004)

Creating markets or decent jobs?:

Group training and the future of work.

Adelaide, Australia: National Centre

for Vocational Education Research.

Castro, C., & Neira, E. (2005)

‘Knowledge transfer: Analysis

of three internet acquisitions.’

International Journal of Human Resources

Management, Vol. 16(1): 120-135. doi:10.1080/0958519042000295993

Cheng, R., Lourenço, F., &

Resnick, S. (2016). Educating graduates

for marketing in SMEs: An update for

the traditional marketing curriculum.

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development 23(2), 495-513. doi:10.1108/JSBED-09-2014-0153

Coen, C. A., & Maritan, C. A.

(2011) ‘Investing in capabilities:

The dynamics of resource allocation.’

Organization Science, Vol. 22(1):

99–117. doi:10.1287/orsc.1090.0524

Cohen, J. (2017). Improving marketing

knowledge among Israeli SMEs using

metaphor- and storyline-based intervention.

Middle-East Journal of Business, 12(3),

10-19. doi:10.5742/ MEJB.2017.92970

Copley, P. (2008) A qualitative research

approach to new ways of seeing marketing

in SME’s: Implications for education,

training and development. Northumbria

Research Link.

Cornelissen, J. P. (2003) ‘Metaphor

as a method in the domain of marketing.’

Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 20(3):

209–225. doi:10.1002/mar.10068

Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2003)

‘Does business planning facilitate

the development of new ventures?’

Strategic Management Journal, Vol.

24(12): 1165-1185. doi:10.1002/smj.349

Dencker, J. C., Gruber, M., &

Shah, S. K. (2009) ‘Pre-entry

knowledge, learning, and the survival

of new firms.’ Organization Science,

Vol. 20(3): 516–537. doi:10.1287/orsc.1080.0387

Devins, D., & Gold, J. (2000).

“Cracking the tough nuts”:

mentoring and coaching the managers

of small firms. Career Development

International, 5(4/5), 250-255.

Devins, D., & Johnson, S. (2002)

‘Engaging SME managers and employees

in training: Lessons from an evaluation

of the ESF Objective 4 Programme in

Great Britain.’ Education+ Training,

Vol. 44(8/9): 370–377. doi:10.1108/00400910210449204

Durgee, J. F., & Chen, M. (2007)

‘22 Metaphors, needs and new