|

Improving Marketing Knowledge among

Israeli SMEs using Metaphor- and Storyline-Based

Intervention

Josef

Cohen

Correspondence:

Josef Cohen

Derby University (U.K)

Phone: +972 (0) 544-205-789

Email:

sticks33@gmail.com

Abstract

The purpose of this mixed-methods

research was to determine the effectiveness

of an intervention for improving marketing

knowledge among managers and employees

of Israeli small and medium-sized

business. This research paper reports

the quantitative data. Small and medium

enterprises (SMEs) contribute to economic

growth and job creation, but have

a high rate of failure compared with

larger organizations. Marketing knowledge

is a key component of SME success,

but, to our knowledge, no marketing

knowledge interventions have been

validated for use in SME environments.

The newly developed intervention programme

by the researcher was designed to

enhance Israeli SMEs' marketing knowledge

and marketing strategy, imparting

new marketing skills and allowing

SMEs to operate with better marketing

knowledge. This study tested the efficacy

of an intervention designed to improve

five dimensions of marketing knowledge

among SMEs using metaphors and storyline

approach through consultant-led training

sessions. Results indicated a significant

improvement (p < .1) in marketing

need awareness, marketing attitudes,

awareness of marketing processes,

and marketing process beliefs, compared

with pre-intervention scores. The

intervention did not result in a significant

change in organizational marketing

skills.

Key words: Marketing knowledge,

Marketing intervention, business failure,

organizational learning, SME, SME

marketing

Introduction

Small and medium enterprises

(SMEs) have a high rate of failure

compared with larger organizations

(Buchanan and Evesson, 2004; Delmar

and Shane, 2003, Honig and Karlsson,

2004; McCartan-Quinn and Carson, 2003).

High SME failure rates are a problem

for the entire economy. SMEs contribute

to economic growth and job creation

(Gilmore et al., 2001; Jones and Rowley,

2011; O'Dwyer et al., 2009), thus

playing an important role in the stability

of national economies (Marom and Lussier,

2014).

Globally, it is estimated that about

half of SMEs fail, with 75% failing

during the first five years (Buchanan

& Evesson, 2004). Other estimates

are even higher. Boyle and Desai (1991)

claimed that 67% of new businesses

fail during the first four years,

and half of start-ups fail during

the first 18 months. Other statistical

data show that the survival rate of

SMEs is country dependent; the survival

rates of SMEs in Australia, Sweden,

and the UK are over 80%; in Italy,

Luxemburg, Finland, and Spain, approximately

70%; and in the United States, less

than 50% (Honig & Karlsson, 2004;

Shane & Delmar, 2004). The literature

strongly suggests that intrinsic factors

such as lack of marketing knowledge

are the major causes of failure, affecting

failure much more than extrinsic factors

such as economy or business competition

(Friedman, 2005; SBA, 2014).

In Israel, a survey conducted in 2013

found that 12% of businesses fail

in their first year of operation (a

larger survival rate compared with

2006 data), and 58% of businesses

fail in their first seven years of

operation (CBS, 2013). The failure

risk assumption for all businesses

in the country is 5.88 on a 1-10 scale.

In comparison, the risk assumption

for SMEs in their first year of existence

is 6.8; this decreases to 6.5 in the

third year and 6.35 in the fifth year.

The reality in Israel is that businesses

with a turnover of less than $2 million

have a 50% likelihood of failing,

which is higher than those with a

larger turnover (BDI-coface, 2006).

All this suggests that Israeli SME

businesses are inherently vulnerable.

Professional advice, including third-party

consulting and intervention, is one

of the strongest predictors of SME

survival (Lussier and Corman, 1995;

Maron and Lussier, 2014). Therefore,

it is crucial from an economic standpoint

to identify the causes of SME failure

and to develop interventions that

can help decrease the number of SME

failures. Tock and Baharub (2010)

stressed the need for an intervention

that effectively educates SME businesses

to use marketing concepts, methods,

and strategies that will enable them

to compete in their field.

Mills (2009) found that using metaphors

to teach students marketing was effective

in improving marketing knowledge and

helped overcome resistance to learning.

Following Mills' finding, the aim

of this study was to test the efficacy

of a short-term, facilitator-led intervention

using metaphors and storyline approach

to improve marketing knowledge among

SME owners and their employees. The

intervention targeted five dimensions

of marketing knowledge: marketing

need awareness, marketing attitudes,

awareness of marketing processes,

marketing process beliefs, and organizational

marketing skills. The purpose of the

research was to answer the question:

Does a metaphor- and storyline-based

intervention program enhance Israeli

SME businesses' marketing knowledge?

The remainder of the article proceeds

as follows. First, we provide background

information on SMEs in Israel and

on SME business marketing, focusing

on defining the five variables of

this study. Next, we describe the

intervention. The setting, sample,

research instrument, and data collection

and analysis procedures are described

in the Methods section. The results

are presented, followed by a discussion

and conclusion.

Background and

literature review

Although small, Israel has an advanced

market economy (Israel Ministry of

Finance, 2012; Marom and Lussier,

2014) with a reputation for successful

SMEs and startups (Israel Ministry

of Finance, 2012). There are approximately

500,000 SMEs in Israel, accounting

for over 99% of all businesses. In

the private sector, these SMEs employ

55% of the nation's workforce, contribute

45% of gross national product, and

provide 15% of exports (Israel Ministry

of Industry, Trade and Labor, 2010).

According to the Israeli Central Bureau

of Statistics (CBS; 2013), SMEs founded

in 2012 created 84,400 new job openings

in Israel (CBS, 2013). For comparison,

in the United States, the largest

economy in the world, 99.7% of businesses

are SMEs; they employ 49.2% of the

workforce in the private sector, provide

64% of new private-sector jobs, and

contribute 33% of export value (Small

Business Administration, 2012). These

data establish the fact that SMEs

make a significant contribution to

the Israeli economy. Decreasing the

rate of SME failure in Israel could

lead to further economic gains.

In Israel, a survey conducted in 2013

found that 12% of businesses fail

in their first year of operation,

and 58% of businesses fail in their

first seven years of operation (CBS,

2013). The failure risk assumption

for all businesses in the country

is 5.88 on a 1-10 scale. In comparison,

the risk assumption for SMEs in their

first year of existence is 6.8; this

decreases to 6.5 in the third year

and 6.35 in the fifth year. The reality

in Israel is that businesses with

a turnover of less than $2 million

have a 50% likelihood of failing,

which is higher than those with a

larger turnover (BDI-Coface, 2006).

SME researchers disagree about the

root causes of SME failure. One of

the best studied models, the Lussier

15 model, proposes 15 variables that

contribute to SME success, including

planning, professional advisors, and

marketing. Empirical research has

provided support for this model among

small businesses in Israel (Maron

and Lussier, 2014), with planning

and professional advice proving to

be particularly strongly associated

with success in that country. Although

there have been conflicting results

across settings and samples using

this model, professional advice has

routinely been an important success

factor (Lussier and Corman, 1995).

This suggests a need to standardize

and structure business consultation

interventions using the latest marketing

knowledge and adjustments according

to businesses' unique characteristics.

Marketing is a key area of interest

for professional advice to SME owners.

In Israel, 24% of surviving SMEs managers

have attributed their successes to

strategic marketing abilities (Friedman,

2005). The importance of marketing

has been confirmed in international

research literature, as well (Bates,

1990; Moutray, 2007; Shane and Delmar,

2004). Strategic marketing is a critical

resource for SME survival, because

it helps managers to compete with

larger businesses (Van Scheers, 2011).

Lack of marketing knowledge contributes

to business problems and aggravates

the state of SME businesses already

in crisis (Jovanov and Stojanovski,

2012; Moutray, 2007). In Israel, there

exist government programs to support

SME survival, but they deal mostly

with the financial aspects of SMEs

(e.g., tax benefits, loans, and direct

financial support), rather than offering

solutions for managerial problems

such as lack of marketing knowledge

(Bennett, 2008). This is increasingly

troubling, as a growing body of research

indicates that small firms find it

difficult to conduct market research,

measure the efficacy of promotions,

and price items (Brouthers et al.,

2015; Denis et al., 2015; Jovanov

and Conevska, 2011). Therefore, there

is a need for an intervention to improve

marketing knowledge among SME owners

and employees.

Dimensions of marketing knowledge

Marketing knowledge is a complicated

construct that may have multiple dimensions.

Additionally, marketing knowledge

is related to concepts of marketing

knowledge utilization (Menon and Varadarajan,

1992) and marketing knowledge management

(Tsai and Shih, 2004), both of which

may be integral to SME success. Because

marketing knowledge is a prerequisite

to the utilization and management

of marketing knowledge, this study

focuses on marketing knowledge itself.

In the following paragraphs, we identify

five dimensions of marketing knowledge

based on a review of SME marketing

literature.

In many cases, SME owners may not

be aware of the need for marketing

in generating market share and cash

flow (Ropega, 2011). If SME owners

exhibit a lack of marketing need awareness,

they may be unlikely to contribute

time and financial resources to marketing

activities, potentially contributing

to business failure. Therefore, marketing

need awareness is one dimension of

marketing knowledge, which could contribute

to SME success.

Even if SME owners are aware of the

need for marketing, they may hold

mistaken marketing attitudes, owing

to an inability to distinguish marketing

and sales as separate business functions.

In effect, many SMEs focus on sales

and are not involved in marketing,

but they may not be aware of this

distinction (McCartan-Quinn and Carson,

2003). Marketing, unlike sales, has

a long-term orientation and focuses

on the development of intangible assets

such as brand awareness. SME owner-managers

may not engage consciously with intangible

assets of their firms, finding tangible

sales efforts easier and more accessible.

However, sales efforts that focus

on short-term gains may not be successful

without a strategic marketing scheme,

so mistaken marketing attitudes could

contribute to SME failure.

The third dimension of marketing knowledge

is awareness of marketing processes.

SME owners who are aware of the need

for marketing strategy as distinct

from sales efforts may still lack

a clear vision for organizational

marketing goals. Relatedly, employees

may not understand the organization's

marketing strategy, making it difficult

for employees to implement that strategy.

This can be understood as a lack of

awareness of marketing processes,

which could lead to unsuccessful implementation

of marketing strategy and, ultimately,

SME failure.

Even when SME owners are aware of

the need for marketing, can distinguish

between marketing and sales, and have

a clear strategic marketing vision

that all employees understand, the

organization's marketing efforts may

be ineffective if the marketing strategy

is based on incorrect marketing process

beliefs (Jovanov and Stojanovski,

2012). For example, the marketing

strategy may be based on the incorrect

belief that marketing is only necessary

when the business has an active need

to attract new customers, or that

customers' response to the business

is essentially determined by the product,

rather than by the way the product

is marketed.

Finally, even the most robust and

well-formed marketing strategy cannot

have a positive effect on business

unless the business has the organizational

marketing skills to ensure that it

is implemented. Organizational marketing

skills are demonstrated by a commitment

to allocating resources, such as funds,

personnel, and knowledge, to strategic

marketing activities (Jones and Rowley,

2011). Marketing knowledge utilization

and management are closely related

to organizational marketing skills

(Menon and Varadarajan, 1992; Tsai

and Shih, 2004). In SMEs, organizational

roles and hierarchies may not be clearly

defined (Cheng et al., 2016), leading

to a failure to implement a marketing

strategy caused by an unclear role

definition and lack of organizational

ability. Therefore, organizational

marketing skill is a fifth dimension

of marketing knowledge.

Organizational learning

Organizational learning makes it possible

for SMEs to improve marketing knowledge

on the individual and organizational

levels. Organizational learning can

be defined as a change in the state

of the organization, stemming from

new knowledge and meanings that are

shared among an organization's members

and may be explicit or implicit (Law

and Chuah, 2015). Research has demonstrated

a connection between organizational

learning and organizational survival

(Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2010).

Organizational learning involves integration

of new learning in the daily conduct

of the organization, with the aim

of improving employee performance,

outcomes, self-efficacy, and openness

to change (Bates and Khasawneh, 2005).

In the business environment, there

may be significant obstacles to organizational

learning, which should be taken into

account in designing interventions

and training programs. Legge et al.

(2007) explored managers' study method

preferences and found that managers

tend to expect quick, practical training;

techniques that involve lengthy lectures

or sentimentality could alienate them

from the learning process. The researchers

also found that managers are frequently

rigid and not open to new learning.

The authors emphasized the importance

of meeting expectations in training

this type of audience to succeed in

marketing education programs (Legge

et al., 2007).

According to Kuster and Vila (2006),

the three most widespread learning

programs in the business and marketing

world are practical exercises, analysis

of cases, and lectures. They found

that the latter two ways of teaching

are ineffective, because they lack

connection to the real business world.

The authors emphasized the great advantage

of using practical exercises because

they are relevant to the reality of

business practice. Jones et al. (2014)

researched SME owners who participated

in a leadership development program

over a two-year period, drawing on

data from 19 focus groups involving

51 participants in Wales. The LEAD

Wales program and factors affecting

it showed that entrepreneurs must

engage in action in order to learn,

and then they may transfer what they

have learned to the organization.

These findings informed the development

of the intervention tested in this

present study.

Intervention using metaphors and

storyline

Based on the review of literature,

the researcher developed an intervention

tool aimed at improving marketing

knowledge along the five dimensions

identified above. The intervention

utilizes the principles of organizational

learning to provide the organization

with adaptive tools that will allow

it to better interact with and exploit

opportunities in the business environment,

thus enhancing survival probability.

The intervention takes the everyday

experience of the participants as

a resource for discussion of marketing

issues; then, the intervention changes

the active knowledge of the participants

by introducing new knowledge about

the experiences discussed, resulting

in change in their level of knowledge

(see Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2010).

In addition, participants are encouraged

to try out their new knowledge when

confronted with actual encounters

with clients in their daily business

activities, and these experiences

are later discussed in the group to

foster more active content learning.

The intervention is a continuous professional

development (CPD; see Fraser et al.,

2007) tool delivered by a trained

consultant who meets with employees

at the SME for a series of four workshop

sessions, each lasting two to three

hours. In these sessions, participants

engage in game-like experiences designed

to teach marketing concepts and tools

for everyday use in the office. In

each workshop, the consultant guides

participants through narratives that

use metaphors of mediaeval times to

bring marketing ideas to learners

in a simplified and colorful manner,

thus encouraging learners to engage

and actively participate in the learning.

The metaphor approach to marketing

knowledge development has been validated

by Mills (2009) and has been shown

to be effective in reducing resistance

to learning (Furst and Cable, 2008).

Following the recommendation of Legge

et al. (2007), the intervention was

designed to be as short as possible,

in order to avoid losing participants'

patience. The goal of the intervention

is to alter SMEs' organizational culture

(see Prajogo and McDermott, 2011)

through organizational learning that

enables participants to acquire experience

and knowledge relevant to marketing

(see Argote and Miron-Spektor, 2010).

The intervention has been piloted

in business settings by the researcher

for the benefit of his clients, but

has not yet been subjected to rigorous

empirical testing to demonstrate its

effectiveness and to evaluate its

outcomes. Therefore, the goal of this

study was to evaluate the intervention

as a structured tool for improving

marketing knowledge among SMEs in

Israel. Because the intervention was

designed to improve marketing knowledge

as measured by five variables, we

hypothesized that participants' scores

in each of these five variables would

increase following intervention. Specifically,

we tested the following hypotheses:

H1: Participants' post-intervention

marketing need awareness scores are

significantly higher than their pre-intervention

marketing need awareness scores.

H2: Participants' post-intervention

marketing attitudes scores are significantly

higher than their pre-intervention

marketing attitudes scores.

H3: Participants' post-intervention

awareness of marketing process scores

are significantly higher than their

pre-intervention awareness of marketing

process skills scores.

H4: Participants post-intervention

marketing process beliefs scores are

significantly higher than their pre-intervention

marketing process beliefs scores.

H5: Participants post-intervention

organizational marketing skills scores

are significantly higher than their

pre-intervention organizational marketing

skills scores.

Methods

Setting and sample

The setting for this study consisted

of SMEs in Israel. We recruited businesses

using a Google Ad-Words advertisement.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

(a) the SME was active in Israel,

(b) a minimum of four employees worked

directly for the SME, (c) the SME

had a minimum monthly turnover of

30,000 ILS, including tax, (d) the

SME was a for-profit organization,

and (e) the SME had been in operation

for less than 10 years. Ten SMEs approached

the researcher in a period of one

month. Three did not qualify; two

stated that they were too busy. Five

qualified and were interested in participating

in the study.

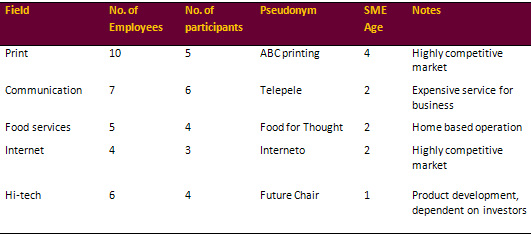

Table 1: Characteristics of research

participants

Not all employees from all organizations

were included. Some were excluded,

as follows. At ABC Printing, five

employees were excluded because they

did not have tenure and did machinery-related

work only. At Telepele, one of the

two investors was not involved in

the daily operations of the business

and was thus excluded. The same was

true of two investors at Future Chair.

Interneto had one technical employee

who just supported the data with no

involvement in the daily operations

and worked from home; this employee

was thus excluded. Food for Thought

had one employee who was only 15 years

old and was thus excluded. This yielded

a final sample size of 22 participants.

Collins et al. (2007) recommended

a minimum sample size of 21 for most

experimental designs and one-tailed

hypotheses. Therefore, the final sample

was adequate to address the research

questions.

Research instrument

To collect data, we administered a

closed-ended questionnaire to measure

five dimensions of marketing knowledge:

marketing need awareness, marketing

attitudes, awareness of marketing

processes, marketing process beliefs,

and organizational marketing skills.

The questionnaire consisted of 18

items measuring the five variables

of interest. All items were scored

on a five-point Likert scale. Because

there were no existing quantitative

research instruments capable of measuring

all variables of interest, we developed

the research instrument, drawing on

concepts from existing literature.

We overcame the disadvantages of using

a new research instrument by conducting

a focus group to ensure face validity.

The focus group consisted of academic

and business colleagues acquainted

with SMEs and marketing concepts.

The purpose of this focus group was

to determine whether the questionnaire

items, in experts' opinion, adequately

captured the variables of interest.

Based on experts' commentary, we made

minor changes to the wording of the

research instrument. However, results

of the focus group suggested that

the questionnaire items were adequate

to measure the five variables.

Data collection

Data collection began in 2009. The

pre-intervention questionnaires were

administered in person just before

the start of the first session of

the intervention. The format of the

intervention sessions was predetermined

by the structure of the intervention.

Sessions took place once a week for

up to 90 minutes. The number of sessions

was also predefined, 4 sessions. Sessions

included both owners and staff at

the SME's business place; setting

and schedule were flexible, based

on participants' preferences. During

the session, the owner and staff were

asked to stop working and detach themselves

from any interference, such as the

telephone, clients, or other business

issues.

Three months after the end of the

4 sessions, post-intervention questionnaires

(consisting of the same research instrument)

were administered, either face-to-face

or via e-mail. This period gave time

for the SMEs to assimilate the intervention's

teachings, and contributed to the

long-term validity of the findings.

The communication with the SME at

this point was informal, via face-to-face

or digital means.

Data analysis

Before analyzing data, I tested for

validity and performed factor analysis

to determine whether the data conformed

to the theoretical model and foundation

of the questionnaire. I also tested

for normality to check whether the

answers were distributed normally,

which enabled the use of parametric

statistics in processing this data

(Beyth-Marom, 1986). The procedures

and results for these validity assessments

are presented in the following paragraphs.

Factor analysis. I conducted

factor analysis using participants'

pre-intervention responses to the

closed-ended questionnaire to negate

the possibility of prior familiarity

with the questionnaire affecting the

response patterns. I conducted exploratory

factor analysis (EFA) using the principal

components method, Varimax rotation,

and 25 iterations. First, the number

of factors was unconstrained by limited

Eigenvalues greater than 1. This resulted

in a factor structure that was not

consistent with the theoretical model.

Therefore, I next performed a factor

analysis constrained to five factors

(corresponding to the five variables

of interest), and this analysis yielded

five distinct factors. These five

factors explained 76% of the variance

in the responses of the interviewees.

This indicates that the response data

corresponded to the theoretical design

of the questionnaire, indicating good

validity.

I calculated Cronbach's alpha values

for each of the five factors. Cronbach's

alpha is a reliability measure that

reflects the extent to which all items

in a questionnaire or scale, measure

the same global content. Index values

range from zero to one, with values

above 0.7 indicating satisfactory

reliability (Rubio, 2009). The reliability

analysis indicated that the level

of reliability of the factors, excluding

the third factor, was higher than

0.7. With regard to the third factor,

there was low reliability (alpha =

0.51). Question 16 was part of this

factor but significantly reduced the

reliability score; therefore, I chose

to omit this question. After removing

question 16, all five factors had

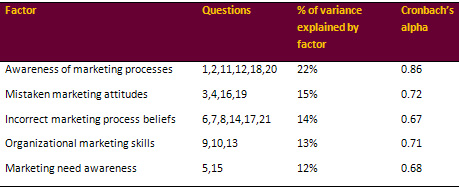

good reliability. These reliability

results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Factor analysis results

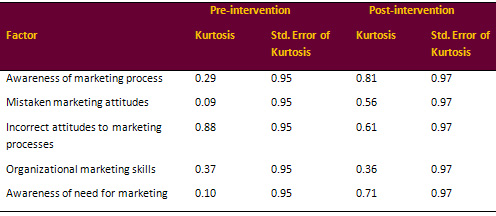

Normality. Parametric tests

of significance, which were part of

the data analysis for this study,

assume that the distribution of the

variables included in the analysis

is normal. To test for normality,

I computed the kurtosis statistic,

which indicates normality as the kurtosis

value approaches 0. The statistical

value divided by its standard error

should also be larger than 2 in absolute

value. Table 3 shows the kurtosis

values and their standard errors for

the pre- and post-intervention results.

Table 3: Normality test results

The findings presented in Table 3

show that all the factors were normally

distributed, so parametric statistics

could be used to analyze the results.

Hypothesis testing.

Quantitative data analysis was

performed using independent sample

t test analyses. These tests allowed

me to test all research hypotheses

by determining whether the means of

answers to the questions varied before

and after the intervention. All quantitative

data analysis was conducted in SPSS

version 20 software.

Results

Sample Demographics

Twenty-two participants completed

the questionnaire before and after

the intervention. The mean age of

the participants was 40.6 (SD = 14.3),

and the median age was 39. Ages ranged

between 15.5 and 71 years. The gender

distribution showed that 50% were

males and 45.5% were females. One

participant did not answer the question

about gender. The majority (63%) of

participants had a college education;

a minority (16%) had only elementary-level

education.

Distribution of answers by variable

is depicted in Figure 1. The marked

effect of the intervention on answers

can be seen visually, especially questions

11, 12, 18 and 20 (awareness of marketing

processes), as well as questions 4

and 14 (incorrect marketing attitudes).

Figure 1: Distribution of answers

by variable

(Click

to view)

Hypothesis Testing

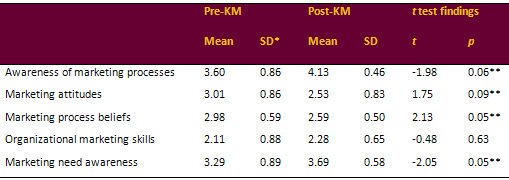

Table 4 lists the values of the five

variables included in the study, before

and after participation in the programme,

as well as the statistical significance

of t tests conducted for difference.

Table 4: Pre/post comparison of

survey variable means

* SD=standard deviation

** Difference in means is significant

at the p < 0.1 level

The first hypothesis stated that the

intervention programme would help

increase awareness of the need for

marketing. After the intervention,

the mean need awareness score increased

from 3.29 to 3.69 (p = .05), indicating

a slight, but significant increase

in awareness of the need for marketing.

Therefore, Hypothesis 5 is accepted.

As a result of participation in the

programme, there was a significant

increase in the level of awareness

of the need for marketing among participants.

The second hypothesis stated that

the intervention programme would help

reduce mistaken marketing attitudes.

After the intervention, the mean mistaken

marketing score decreased from 3.01

to 2.53 (p = .09), indicating a moderate

decrease in mistaken marketing attitudes.

Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is accepted.

As a result of participation in the

programme, there was a significant

decrease in the level of mistaken

marketing attitudes.

The third hypothesis stated that the

intervention programme would help

increase awareness of marketing processes.

After the intervention, the mean awareness

score increased from 3.60 to 4.13

(p = .06), indicating a significant,

increase in awareness of marketing

processes. Therefore, Hypothesis 1

is accepted. As a result of

participation in the programme, there

was a significant rise in the level

of awareness of the marketing process.

The fourth hypothesis stated that

the intervention programme would help

reduce incorrect beliefs about marketing

processes. After the intervention,

the mean score for this variable decreased

from 2.98 to 2.59 (p = .05), indicating

a slight, yet significant decrease

in incorrect attitudes toward marketing

processes.

Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is accepted.

As a result of participation in the

programme, there was a significant

decrease in the level of incorrect

attitudes toward marketing processes.

The fifth hypothesis stated that the

intervention programme would help

improve organisational marketing skills.

Although there was a very slight increase

in organisational marketing scores

(from 2.11 to 2.28), the results of

the t test indicated that this result

was non-significant. Therefore, Hypothesis

4 is rejected. There was no

change in the organisation's perceived

marketing skills before and after

the intervention.

Additional Observations

Before the intervention, although

the employees had a high level of

awareness about the marketing process,

they displayed moderately incorrect

attitudes about marketing and marketing

procedures. Furthermore, their awareness

of the need for marketing was mediocre,

and the level of their organisational

skills for creating a marketing process

was low.

Interestingly, the standard deviations

for all factors except marketing attitudes

were lower after participation in

the intervention. This finding could

be interpreted as an indicator that

gaps in knowledge about marketing

issues and practices diminished after

the intervention, thus causing the

organizations to be more homogenous

in marketing knowledge. These findings

are discussed in further detail in

the following section.

Discussion

The results demonstrated that, among

this research sample, the intervention

increased scores for four of the five

dimensions of marketing knowledge:

marketing need awareness, marketing

attitudes, awareness of marketing

processes, and marketing process beliefs.

This finding is in accordance with

existing literature related to continued

professional development and organizational

learning. Scholars have suggested

that metaphoric language can be useful

in teaching new concepts to adults

(Bremer and Lee, 2007; Cornelissen,

2003; Durgee and Chen, 2006; Fillis

and Rentschler, 2008; Mills, 2009).

Additionally, organizational learning

can take place in a group setting

and that social learning can reduce

mistaken marketing attitudes since

members of the group can assist each

other in learning (Fraser et al.,

2007; Van Lange et al., 2011; Wenger,

2000).

The researcher did not observe a significant

change in organizational marketing

skills following the intervention.

In some ways, this finding accord

with existing literature suggesting

that organizational culture is very

difficult to change and that change

usually takes place on a surface level,

without penetrating to the level of

values and assumptions (Schein, 1990).

However, scholars have suggested that

it is possible to change organizational

behavior through training over time

(Berson et al., 2008). Future research

should focus on understanding barriers

to organizational change and ways

to overcome those barriers through

intervention, perhaps using qualitative

approaches.

The literature indicates that SMEs

have unique characteristics distinguishing

them from larger businesses. On the

one hand, these characteristics contribute

to their existence and growth (e.g.,

through their agility in business

conduct), but, on the other hand,

the same characteristics threaten

SMEs' survival. The literature suggests

that lack of marketing knowledge among

SMEs causes a large number to fail

prematurely (Buchanan and Evesson

2004; Boyle and Desai, 1991; BDI-Coface,

2006). The results of this study coincide

with existing research, particularly

with respect to the notion that, in

SMEs, the line between sales and marketing

is often blurred, leading to an overemphasis

on sales and a detrimental de-emphasis

of marketing (McCartan-Quinn and Carson,

2003).

Scholars (e.g., Barney, 1986; Xenikou

and Simosi, 2006) have continually

suggested that a lack of ability to

use marketing tools in daily business

can harm SMEs' ability to adapt to

the business environment. However,

research indicates that professional

advice, including interventions in

the form of continued professional

development, can contribute to SME

success over the long term (Maron

and Lussier, 2014). Therefore, a validated

marketing intervention is needed to

improve SMEs' marketing knowledge

and ability, thereby promoting their

success and contributing to national

economies.

This study was, to our knowledge,

the first to test a standardized marketing

intervention designed specifically

for SMEs. There were several limitations

that should be taken into consideration.

First, as an exploratory study, it

was based on a convenience sampling

method. It is not unlikely, therefore,

that the sample is biased in the sense

that it included organizations that

were actively seeking change. This

sampling method reduces the generalizability

of the findings. The small number

of individual participants also limits

generalizability. A further limitation

of the research stems from the fact

that the design of the intervention

program and its evaluation were both

carried out by the same researcher.

Therefore, once again, there is the

possibility of evaluating bias in

the data and in reported findings,

caused by the professional involvement

of the researcher with the research

topic. Relatedly, the small sample

of participants working directly with

the researcher during the intervention

may have led to social desirability

bias in participants' responses (Weisberg,

2005). Every effort was made to limit

bias during the research process,

but future research should attempt

to replicate our results in other

settings. Additionally, longer term

follow-up is needed to verify that

increases in marketing knowledge that

result from the intervention in fact

lead to improved business outcomes.

Conclusions

The current study provides preliminary

evidence that the metaphor- and storyline-based

intervention is an effective CPD program

for SMEs. Tock and Baharub (2010)

stressed the need for an intervention

that effectively educates SME businesses

to use marketing concepts, methods,

and strategies that will enable them

to compete in their field, Mills stressed

that metaphors may be a useful tool

for teaching marketing (Mills, 2009).

The intervention and similar tools

could be a solution to the reported

paucity of practical marketing information

for SMEs (Reijonen, 2010; Simpson

et al., 2006; Walsh and Lipinski,

2009), because the intervention presents

a way of making marketing methods

accessible while accommodating the

specific marketing needs of participant

organisations.

Given these findings, metaphor- and

storyline-based intervention appears

to have strong utility and could be

used beneficially in other SME settings

or by practitioners. However, the

study also revealed some areas which

warrant further development of such

interventions. In particular, it was

not clear that the intervention led

to lasting results in organizational

culture in the form of organizational

marketing skills. Therefore, there

is room for improvement of the intervention

tool in order to better enable the

demonstrated improvements in marketing

knowledge to translate into lasting,

fundamental changes in the organizational

culture.

References

Argote, L., & Miron-Spektor, E.

(2011). Organizational learning: From

experience to knowledge. Organization

Science, 22(5), 1123-1137. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0621

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational

culture: Can in be a source of sustained

competitive advantage? Academy of

Management Review 11(3), 656-665.

doi:10.5465/AMR.1986.4306261

Bates, R. & Khasawneh, S. (2005).

Organizational learning culture, learning

transfer climate and perceived innovation

in Jordanian organizations. International

Journal of Training and Development

9(2), 96-109. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2419.2005.00224.x

Bates, T. (1990). Entrepreneur human

capital inputs and small business

longevity. The Review of Economics

and Statistics 72(4), 551-559. doi:10.2307/2109594

BDI-Coface. (2006). Survival of small

businesses in Israel: Special report

for the Israeli Agency for small and

medium enterprises.

Bennett, R. (2008). SME policy support

in Britain since the 1990s: What have

we learnt? Environment and Planning

C: Government and Policy 26(2), 375-297.

doi:10.1068/c07118

Berson, Y., Oreg, S., & Dvir,

T. (2008). CEO values, organizational

culture and firm outcomes. Journal

of Organizational Behavior 29(5),

615-633. doi:10.1002/job.499

Beyth-Marom, R. (1986). Research methods

in social sciences (Vol. 3) Israel:

Open University.

Boyle, R. D. & Desai, H. B. (1991).

Turnaround strategies for small firms.

Journal of Small Business Management

29(3), 33-42.

Bremer, K. & Lee, M. (1997). Metaphors

in marketing: Review and implications

for marketing. Advances in Consumer

Research 24, 419-424.

Brouthers, K. D., Nakos, G. &

Dimitratos, P. (2015). SME entrepreneurial

orientation, international performance,

and the moderating role of strategic

alliances. Entrepreneurship Theory

and Practice 39(5), 1161-1187. doi:10.1111/etap.12101

Buchanan, J. & Evesson, J. (2004).

Creating markets or decent jobs?:

Group training and the future of work.

Adelaide, Australia: National Centre

for Vocational Education Research.

Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel.

(2013). Business demography and survival

[Press release].

http://www.cbs.gov.il/publications16/1636_business_demography_2014/pdf/intro_e.pdf

(accessed 5th August 2015).

Cheng, R., Lourenço, F., &

Resnick, S. (2016). Educating graduates

for marketing in SMEs: An update for

the traditional marketing curriculum.

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development 23(2), 495-513. doi:10.1108/JSBED-09-2014-0153

Collins, K. M., Onwuegbuzie, A. J.,

& Jiao, Q. G. (2007). A mixed

methods investigation of mixed methods

sampling designs in social and health

science research. Journal Of Mixed

Methods Research 1(3), 267-294. doi:10.1177/1558689807299526

Cornelissen, J. P. (2003). Metaphor

as a method in the domain of marketing.

Psychology & Marketing 20(3),

209-225. doi:10.1002/mar.10068

Delmar, F. & Shane, S. (2003).

Does business planning facilitate

the development of new ventures? Strategic

Management Journal 24(12), 1165-1185.

doi:10.1002/smj.349

Denis, J. C., Kumar, D., Yusoff, R.

M., & Imran, A. (2015). Modelling

market orientations for SME performance.

Jurnal Teknologi 77(22) doi:10.11113/jt.v77.6663

Durgee, J. F. & Chen, M. (2007).

22 Metaphors, needs and new product

ideation. Handbook of Qualitative

Research Methods in Marketing, 291.

Fillis, I. & Rentschler, R. (2008).

Exploring metaphor as an alternative

marketing language. European Business

Review 20(6), 492-514. doi:10.1108/09555340810913511

Fraser, C., Kennedy, A., Reid, L.,

& McKinney, S. (2007). Teachers'

continuing professional development:

Contested concepts, understandings

and models. Journal of In-Service

Education 33(2), 153-169. doi:10.1080/13674580701292913

Friedman, R. (2005). Israeli SME Data.

Israeli Agency for Small and Medium

Enterprises.

Furst, S. A. & Cable, D. M. (2008).

Employee resistance to organizational

change: Managerial influence tactics

and leader-member exchange. Journal

of Applied Psychology 93(2), 453-462.

doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.453

Gilmore, A., Carson, D., & Grant,

K. (2001). SME marketing in practice.

Marketing Intelligence & Planning

19(1), 6-11. doi:10.1108/02634500110363583

Honig, B. & Karlsson, T. (2004).

Institutional forces and the written

business plan. Journal of Management

30(1), 29-48. doi:10.1016/j.jm.2002.11.002

Israel Ministry of Finance. (2012).

The Israeli economy: Fundamentals,

characteristics and historic overview.

Retrieved from http://www.financeisrael.mof.gov.il/FinanceIsrael/Docs/En/The_Israeli_Economy_2012.pdf

Israel Ministry of Industry, Trade

and Labor. (2010). Israel: Global

center for breakthrough innovation.

Retrieved from http://www.moital.gov.il/NR/rdonlyres/D20FF2AA-23AA-4D5F-8D44-8CD1DD61127B/0/Innovationbrochure2010.pdf

Jones, K., Sambrook, S. A., Pittaway,

L., Henley, A., & Norbury, H.

(2014). Action learning: How learning

transfers from entrepreneurs to small

firms. Action Learning: Research and

Practice 11(2), 131-166. doi:10.1080/14767333.2014.896249

Jones, R. & Rowley, J. (2011).

Entrepreneurial marketing in small

businesses: A conceptual exploration.

International Small Business Journal

29(1), 25-36. doi:10.1177/0266242610369743

Jovanov, T. M. & Stojanovski,

M. (2012). Marketing knowledge and

strategy for SMEs: Can they live without

it?. Thematic Collection of papers

of international significance: "Reengineering

and entrepreneurship under the contemporary

conditions of enterprise business",

131-143.

Jovanov, T. & Conevska, B. (2011).

Comparative analysis of factors from

marketing and legal perspective and

policies that affect SMEs in Macedonia

and EU. In Conference proceedings,

economic development and entrepreneurship

in transition economies: A Review

of Current Policy Approaches (477-490).

Faculty of Economics, University of

Banja Luka.

Küster, I. & Vila, N. (2006).

A comparison of marketing teaching

methods in North American and European

universities. Marketing Intelligence

& Planning Journal 24(4), 319-331.

doi:10.1108/02634500610672071

Law, K. M. & Chuah, K. B. (2015).

Organizational learning as a continuous

process, DELO. In PAL driven organizational

learning: Theory and practices (7-29)

Springer International Publishing.

Legge, K., Sullivan-Taylor, B. &

Wilson, D. (2007). Management learning

and the corporate MBA: Situated or

individual? Management Learning 38(4),

440-457. doi:10.1177/1350507607080577

Lussier, R. N. & Corman, J. (1995).

There are few differences between

successful and failed small businesses.

Journal of Small Business Strategy

6(1), 21-34.

McCartan-Quinn, D. & Carson, D.

(2003). Issues which impact upon marketing

in small firms. Small Business Economics

21(2), 201-213. doi:10.1023/A:1025070107609

Marom, S. & Lussier, R. N. (2014).

A business success versus failure

prediction model for small businesses

in Israel. Business and Economic Research

4(2), 63. doi:10.5296/ber.v4i2.5997

Menon, A. & Varadarajan, P. R.

(1992). A model of marketing knowledge

use within firms. The Journal of Marketing:

53-71. doi:10.2307/1251986

Mills, M. K. (2009). Seeing jazz:

Doing research. International Journal

of Market Research 51(3), 383-402.

doi:10.2501/S147078530920061X

Moutray, C. (2007). The small business

economy for data year 2006: A report

to the president. Washington, DC:

United States Government Printing

Office.

O'Dwyer, M., Gilmore, A., & Carson,

D. (2009). Innovative marketing in

SMEs. European Journal of Marketing

43(1/2), 46-61. doi:10.1108/03090560910923238

Prajogo, D. I. & McDermott, C.

M. (2011). The relationship between

multidimensional organizational culture

and performance. International Journal

of Operations & Production Management

31(7), 712-735. doi:10.1108/01443571111144823

Reijonen, H. (2010). Do all SMEs practise

same kind of marketing? Journal of

Small Business and Enterprise Development

17(2), 279-293. doi:10.1108/14626001011041274

Ropega, J. (2011). The reasons and

symptoms of failure in SME. International

Advances in Economic Research 17(4),

476-483. doi:10.1007/s11294-011-9316-1

Rubio, I. (2009). SPSS Manual. Israel:

Open University.

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational

culture. American Psychologist 45(2),

109-119. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.109

Shane, S. & Delmar, F. (2004).

Planning for the market: Business

planning before marketing and the

continuation of organizing efforts.

Journal of Business Venturing 19(6),

767-785. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.11.001

Simpson, M., Padmore, J., Taylor,

N., & Frecknall-Hughes, J. (2006).

Marketing in small and medium sized

enterprises. International Journal

of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research

12(6), 361-387. doi:10.1108/13552550610710153

Small Business Administration. (2012).

Frequently asked questions about small

business. SBA Office of Advocacy.

Retrieved from http://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/files/Finance%20FAQ%208-25-11%20FINAL%20for%20web.pdf

Tock, J. M. & Baharun, R. (2013).

Introduction to SMEs in Malaysia:

Growth potential and branding strategy.

World Journal of Social Sciences 3(6),

189-203.

Tsai, M. T. & Shih, C. M. (2004).

The impact of marketing knowledge

among managers on marketing capabilities

and business performance. International

Journal of Management 21(4), 524.

Van Scheers, L. (2011). SMEs' marketing

skills challenges in South Africa.

African Journal of Business Management

5(13), 5048-5056.

Walsh, M. F. & Lipinski, J. (2009).

The role of the marketing function

in small and medium sized enterprises.

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development 16(4), 569-585. doi:10.1108/14626000911000929

Weisberg, H. F. (2005). The Total

Survey Error Approach. Chicago: University

of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226891293.001.0001

Wenger, E. (2000). Communities of

practice and social learning systems.

Organization 7(2), 225-246. doi:10.1177/135050840072002

Xenikou, A. & Simosi, M. (2006).

Organizational culture and transformational

leadership as predictors of business

unit performance. Journal of Managerial

Psychology 21(6), 566-579. doi:10.1108/02683940610684409

|